What is shaking conservative parties today is not ideology itself. It is the style of governance.

As far-right impulses become more visible, something more basic begins to unravel—compromise, procedure, and accountability. The minimum conditions for rational politics are no longer reliably held. And the same scene repeats: the party hardens, institutions strain, and governing capacity thins out.

In the end, it becomes one dilemma.

Move further right to hold the hardline base, and the middle walks away. Governing becomes harder. Legitimacy narrows. Step back toward the center, and the base sees it not as an adjustment but as a betrayal. The organization shakes from within. Conservative parties in both the United States and South Korea are now trapped in this equation, unable to solve it cleanly.

Washington recently offered a vivid example.

During the federal appropriations vote, Republicans did not look like a party trying to govern. They looked like a party tolerating division. After experiencing the longest shutdown in U.S. history, there was a shared understanding that even a partial shutdown had to be avoided. The incentive was obvious. The cost of failure was obvious.

And yet leadership could not unify the party. Internal disagreement remained unresolved. The result was predictable: a partial shutdown began on January 31. Several House Republicans even broke with their own party line and voted no, tightening the knot instead of loosening it.

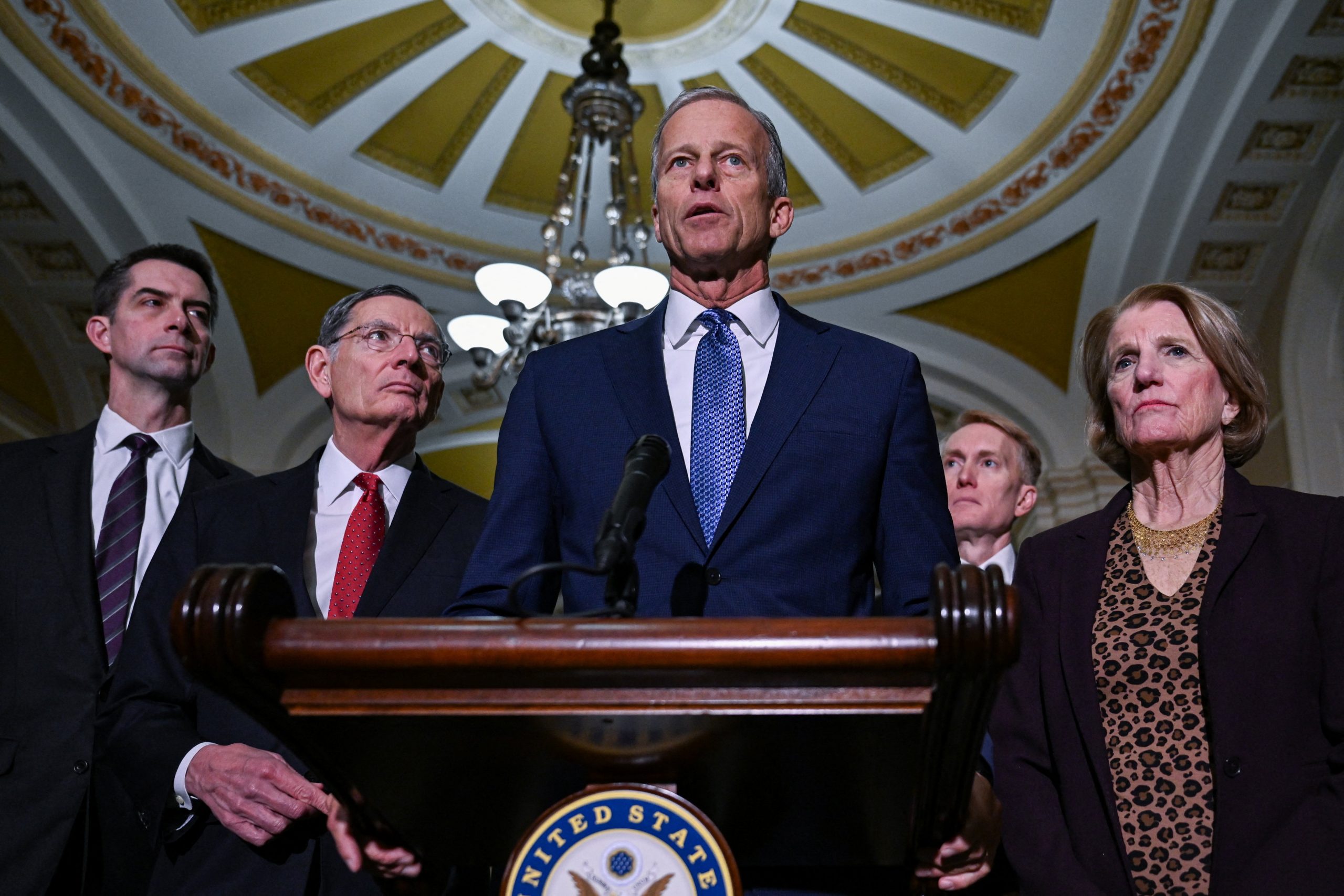

President Donald Trump attempted a last-minute mediation. He tried to attach a health-insurance-related reform measure to the spending package, as if to create a bargaining wedge that could move Democrats. But it failed to generate momentum. Senate Republican Leader John Thune, in particular, held a hardline position and showed little appetite for compromise.

That leads to the essential question.

Why would a party accept the costs of dysfunction—politically, financially, institutionally—rather than pursue a workable deal?

The answer is not personal. It is structural.

In an era of polarization, parties are no longer driven by the preferences of the middle. They are driven by the intensity of the edge. The most ideologically committed supporters vote more reliably. They fight louder online. They donate more aggressively. They become the most organized segment of the party ecosystem—and therefore the most powerful.

MAGA has deepened this dynamic. It has turned a political alignment into a form of identity. Under that condition, shifting tone or modifying policy is no longer read as a strategy. It is read as disloyalty.

And when moderation becomes disloyalty, the party cannot govern normally.

This is why the Republican coalition has reordered itself. The neoconservatives who once formed the backbone of Republican power—from the Reagan years through George W. Bush—have largely been pushed aside. “Reasonable conservatism,” once considered a public-facing strength, is now treated as a vulnerability inside the party’s own incentive structure.

But rationality does not disappear simply because a base becomes louder.

In fact, the need for it grows.

Hardline mobilization can win headlines and even win primaries. It can deliver short-term unity through anger. But it cannot easily deliver broad legitimacy. And once moderate voters begin to peel away in earnest, a party’s coalition does not just weaken—it shrinks rapidly.

Recent polling suggests precisely that: the middle is drifting toward Democrats. That shift matters because elections, especially close ones, are decided by late-deciding moderates. If the center hardens into a Democratic-leaning bloc, conservatives may not merely lose the next contest. They may lose their long-term political floor.

South Korea is not immune to the same logic.

Its largest conservative party, the People Power Party, has entered a deeper phase of internal conflict since the expulsion of former leader Donghoon Han. Yet Chairman Donghyeok Jang retains notable support. One explanation is organizational stability, particularly finances.

In roughly three months after taking office, the number of dues-paying “responsible members,” those contributing at least 1,000 won per month, reportedly increased by more than 200,000. As of last month, total party membership exceeded one million. By the standards of South Korean conservative party history, this is unprecedented.

But membership growth is not the same as political expansion. A party can gain members while becoming smaller in every way that matters.

The People Power Party, at the same time, is showing signs of contraction. It claims to acknowledge wrongdoing related to the martial law crisis, yet it has not clearly severed ties with former President Yoon Suk-yeol. That ambiguity inevitably returns as a question of credibility. Reform-minded lawmakers criticize the leadership. The party’s internal tension rises.

Which means the real question is not the raw number of members.

It is what kind of party those members are building.

Has the party broadened its coalition? Or has an energized hardline bloc tightened its grip—binding the party into a narrower lane, making any turn toward rationality even more costly?

If the answer is the latter, the dilemma only deepens. And that is the point where the United States and South Korea look strikingly similar.

A conservative party that embraces only its hardline base may survive the next round. It may even win short-term victories. But it will grow more distant from the middle—and more incapable of governing. Yet a conservative party that tries to recover rationality must draw boundaries against extremism. It must restore norms of negotiation and accountability. And the moment it attempts that, its internal foundation is threatened.

The choice, then, is not between strength and weakness. It is between short-term stability and long-term survival.

Because in the long run, no party can govern effectively on identity politics alone. No party can build a durable majority by shrinking its own coalition. And no democracy can sustain itself when compromise is treated as failure.

If conservative parties want to endure, the answer is ultimately straightforward.

They must resist the pull of far-right radicalization. They must return to a politics where common sense, policy competence, and negotiation still function. Otherwise, conservative politics will not only become narrower.

It will become ungovernable.

BY KYEONGJUN KIM [kim.kyeongjun1@koreadaily.com]

![Six Korean American athletes chase Olympic glory at Milan Winter Games Korean American athletes competing for Team USA at the 2026 Winter Olympics. Clockwise from top left: Chloe Kim, Bea Kim, Andrew Heo, Brandon Kim, Eunice Lee, and Mystique Ro. [Reuters / Team USA website]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/0204-Olympics-100x70.jpg)

![Armed federal agents raid church during community service event, sparking outrage Federal agents arrest Carlos Chavez at Northridge United Methodist Church on January 29. [ABC7 screenshot]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/0204-church-100x70.jpg)