By Joseph Juhn

The author is a documentary filmmaker of “Jeronimo” and “Chosen”.

[First of three-part series column]

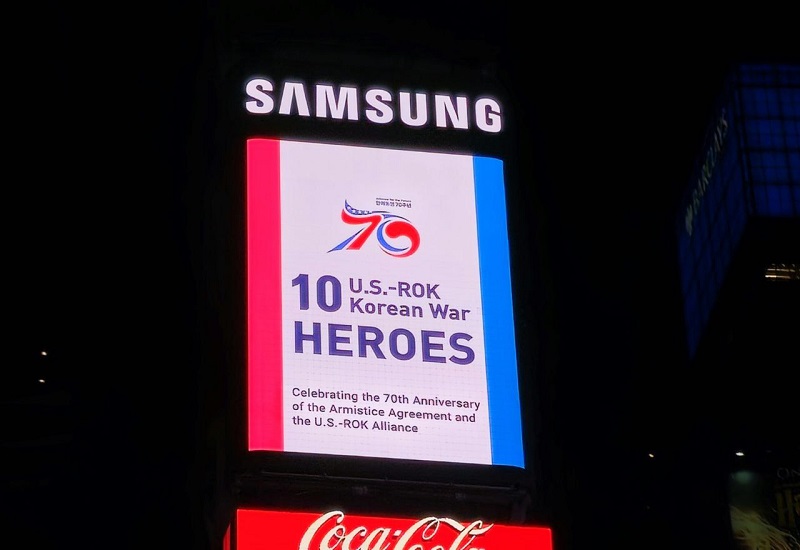

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the U.S.-ROK alliance, and events are unfolding across the United States, led by the South Korean (Republic of Korea) government. The relationship between the two countries, which originated with the military and security focus of the U.S.-South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty, has now expanded to encompass various domains, including economics, science, culture, and public diplomacy.

As a documentary filmmaker who has explored the stories of the Korean diaspora through works like “Jeronimo” and “Chosen,” I have had the opportunity to participate in many of these events, both as an audience member and a presenter. However, it is crucial to ponder the “narrative” associated with a particular anniversary: why it matters and what lends it significance.

Born and residing in the United States, I spent my childhood and adolescence in South Korea, maintaining close ties with my parents and many friends there. Hence, I have every reason to embrace the strengthening bond between South Korea and the United States.

Yet, I’ve noticed a prevailing narrative in the “70th anniversary of the U.S.-ROK alliance” events. This narrative focuses on the sacrificial contributions of the United States during the Korean War, the achievements of our first president in defending liberal democracy against communism, and the rapid development of South Korea into a developed nation with U.S. economic and security assistance.

Undoubtedly, it’s a narrative we can take pride in. However, hearing the same story repeatedly led me to reflect on its selective and incomplete logic, along with its philosophical and moral inadequacies. As an elderly man once remarked, questioning fosters intelligence, and through critical thinking, I began to search for a narrative beyond national and ideological frameworks.

At a Princeton University event in May, several professors argued that contemplating the 70th anniversary of the U.S.-ROK alliance should commence with the 1882 Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, not the year 1953. In other words, we need a more sober and objective view of the U.S. role on the Korean Peninsula during the “other” 70 years from 1882 to 1950.

They pointed out instances where the United States had failed to protect the country from foreign aggression prior to the Korean War, such as the 1905 Taft-Katsura Pact, in which Japan tolerated U.S. colonization of the Philippines, and the U.S. tolerated Japan’s invasion of Korea and rule over the Korean Peninsula. This serves as a reminder to exercise caution in making hasty value judgments and to acknowledge the variable and complex nature of international relations, which evolves with national interests and the course of history.

While blood ties and national development rooted in the sacrifices of countless people are commendable, I believe that in 2023, the narrative underpinning the U.S.-ROK alliance should not be confined to the ideological framework of “anti-communism” or “the triumph of liberal democracy.” Such a rhetoric may be diplomatic and political, but it fails to align with the level of intellectual thinking and contemporary concerns of the people of both countries.

Some might consider this approach naive, given the cold reality of international relations, including the potential escalation of a new Cold War between the United States and China. However, in times like these, shouldn’t we envision a more transcendent narrative?

A narrative centered on humanity and universality, one that transcends the triumphs of past ideological conflicts. I find such a narrative in the concept of “diaspora,” an academic term that once referred to Jews wandering outside of Palestine but now pertains to anyone living outside their country of origin. I propose applying this concept in a moral, philosophical, and humanistic sense, not merely a geographical one. In other words, diaspora, as I interpret it, encompasses not only Korean Americans living in the United States but also “the foreign, hybrid, and minority perspectives and identities that exist within a society of diverse people.”

What if we explored the narrative of the U.S.-Korea alliance not solely through the lens of ideology but through the history, stories, and consciousness of the more than two million Korean Americans who arrived in Hawaii in 1903? Going forward, over the next two columns, I would like to contemplate the narrative of the 70th anniversary of the U.S.-Korea alliance through the creative lens of Korean immigrants’ ways of being.