Sent Back, Left Behind:

Korean Lives After U.S. Deportation

Expelled from America returning to a country that calls them citizens yet gives them no place to belong

By Yeol Jang and Yoonjae Jung

Photography by Sangjin Kim

For years, sometimes for decades, their lives were rooted in the United States. Then a single legal category, their immigration status, determined everything. Sent back to Korea, the country of their birth, they found no familiar ground left to return to. For those who returned by choice or by force, Korea was no longer their country.

This article follows deportees now living in a Korea that feels newly foreign, tracing how they rebuild daily life without ever fully finding a place to belong. Except for those who agreed to be identified by their full names, identities have been abbreviated at their request.

Returning to a Homeland That No Longer Knows Them

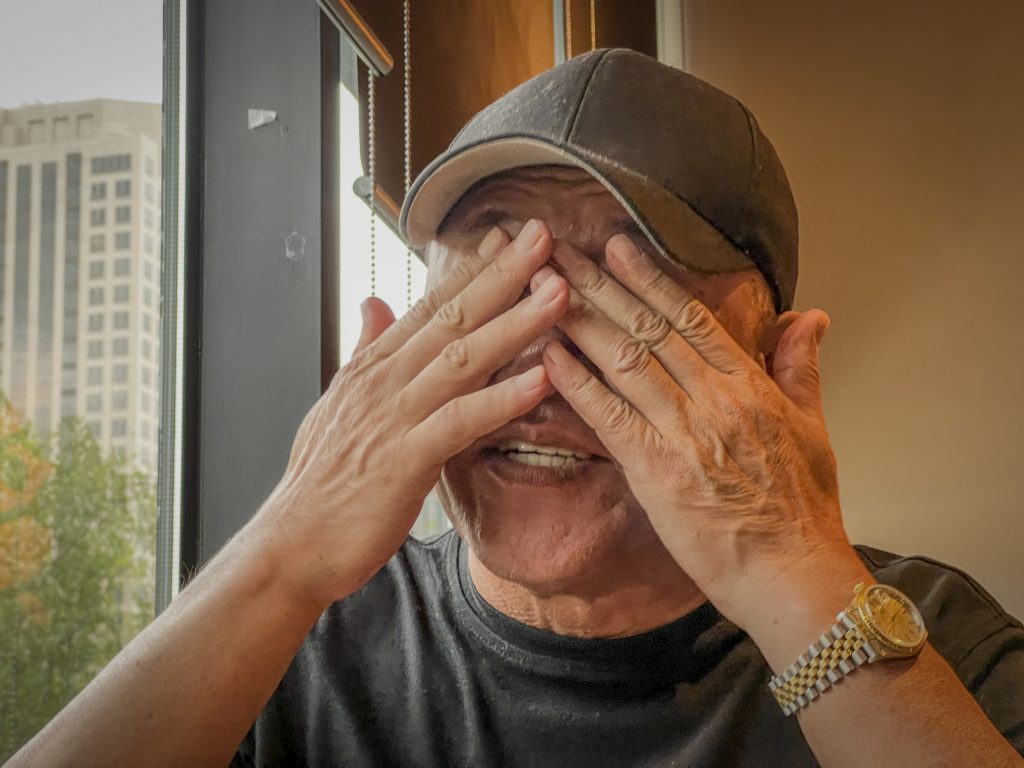

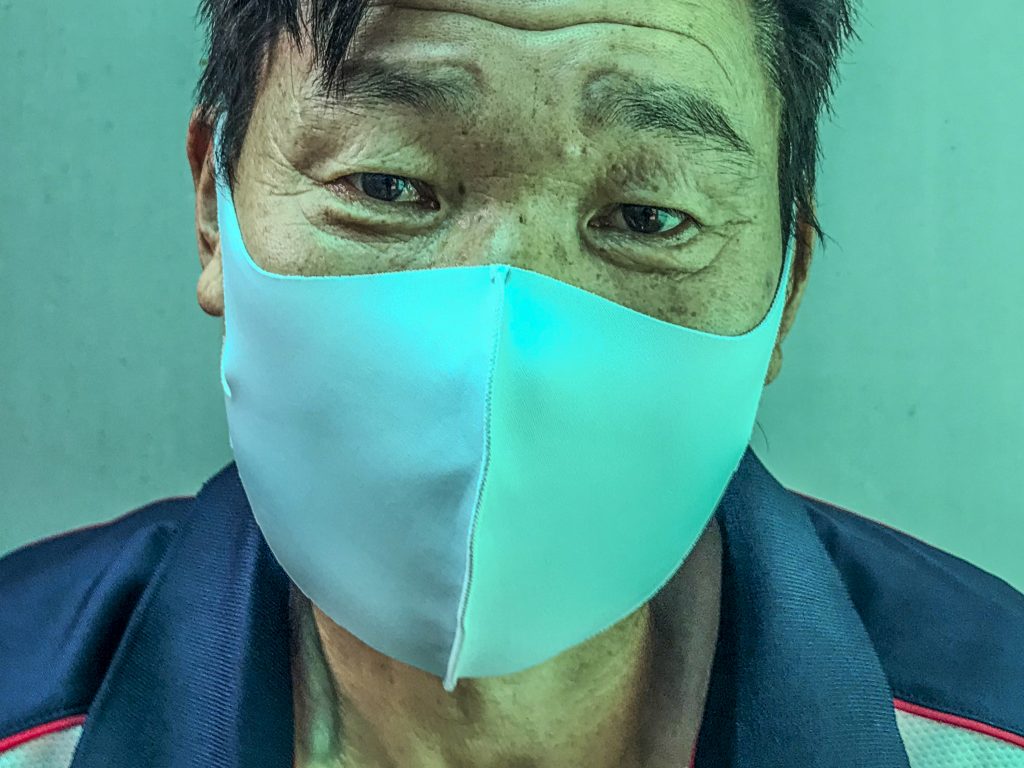

Seventy-year-old Chae Byeong-rok was very much alive in New York until recently, yet in Korea he was listed as “deceased.” When he arrived at the shelter run by the World Cross Mission in Yeoju, he learned that no official records of him remained. He is now pursuing a lawsuit to restore his family registry.

Chae first left for the United States in 1999. During Korea’s financial crisis, when making a living became increasingly difficult, he boarded a plane to America without a clear plan and without a valid visa. Entering the country as a tourist was, for him, a last attempt at survival.

Life without legal status was precarious. Chae supported himself through day labor, mainly carpentry and other temporary jobs, and avoided discussing the family he had left behind. His status as “deceased” in Korea stems from the long period during which he lost contact with them; believing he had died, they eventually filed a death report. Now, more than twenty years later, his return has set in motion a legal effort to reclaim his identity.

“Without a Social Security number, of course, I couldn’t open a bank account,” Chae said. He described a life built around what was available rather than what was possible. He was paid in cash for day labor jobs and kept his expenses low. “I lived honestly. I never committed a crime. I even applied for an ITIN and paid taxes for about seven years.”

Yet legal reality did not bend to intention. However carefully he lived, he remained undocumented, and that status shaped every part of his life.

The impact became sharper during the pandemic. As businesses closed and daily routines halted, he found himself excluded from all forms of government assistance. Age made physical labor more difficult, and each month felt harder than the one before.

“When the Trump administration came in, the pressure on people like me just grew and grew,” he said. “I felt something tightening around me. I was scared to even go outside. It felt like doing the right thing no longer mattered.”

Eventually, he made a decision he had resisted for years: he would leave the United States on his own terms, before ICE did it for him.

But leaving was not simple. Because he was officially recorded as deceased in Korea, he could not obtain a valid Korean passport. Only with help from the Korean Consulate General in New York was he able to secure a temporary passport and buy a ticket home.

Before boarding, he paused in the airport bathroom, looking at a version of himself he barely recognized.

“The young man who came to America was gone,” he said quietly. “Only an old, tired man was left.”

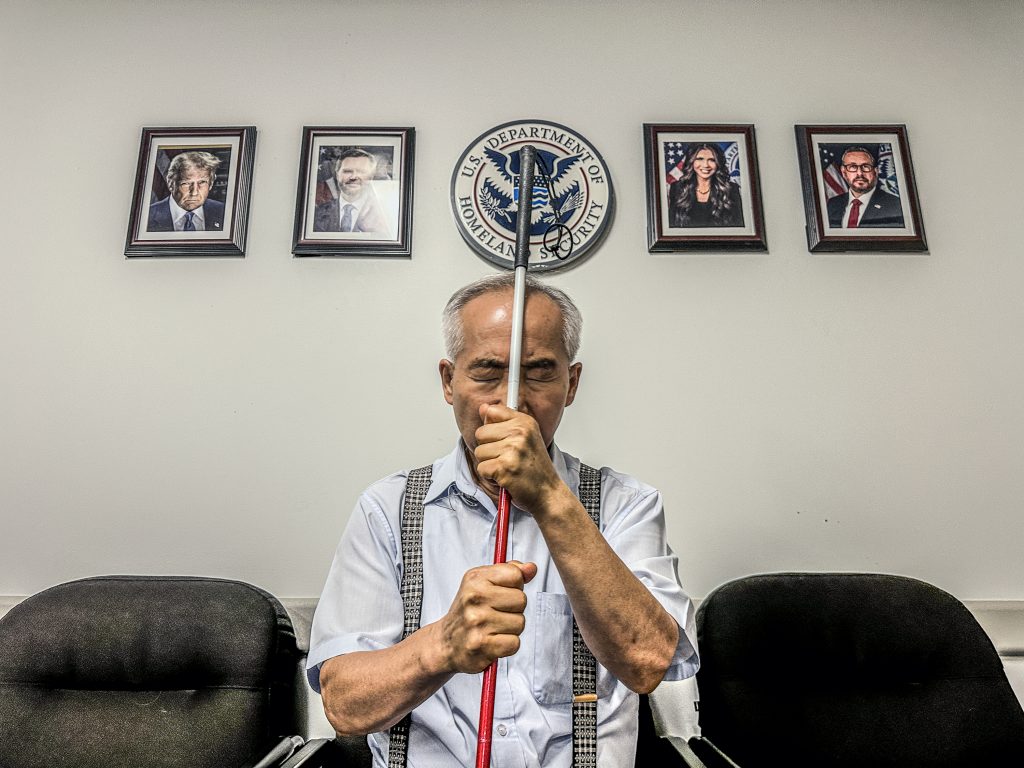

The shelter where Chae now lives is run by Pastor Ahn Il-kwon, who has spent more than three decades receiving people who arrive from the United States with nowhere else to go. Ahn is 80 and blind, yet he speaks of deportees with a familiarity shaped by long experience rather than sentiment.

“Think about it,” he said. “They are not fully accepted in the United States, and when they come here, Korea doesn’t really know what to do with them either. Leaving behind your whole life in a day—that leaves a wound.”

Since opening the shelter in 1989, Ahn estimates that roughly 500 deportees have passed through its doors. In recent years, he noted, the number has grown. His daily work is modest—food, a bed, assistance with paperwork when possible—but the consistency of it is what many residents rely on.

About thirty people currently live at the shelter. Some are deportees who, like Chae, returned after decades abroad. Others are dealing with addiction or mental illness. The shelter is a small, improvised community on a hillside in Yeoju, held together less by structure than by need.

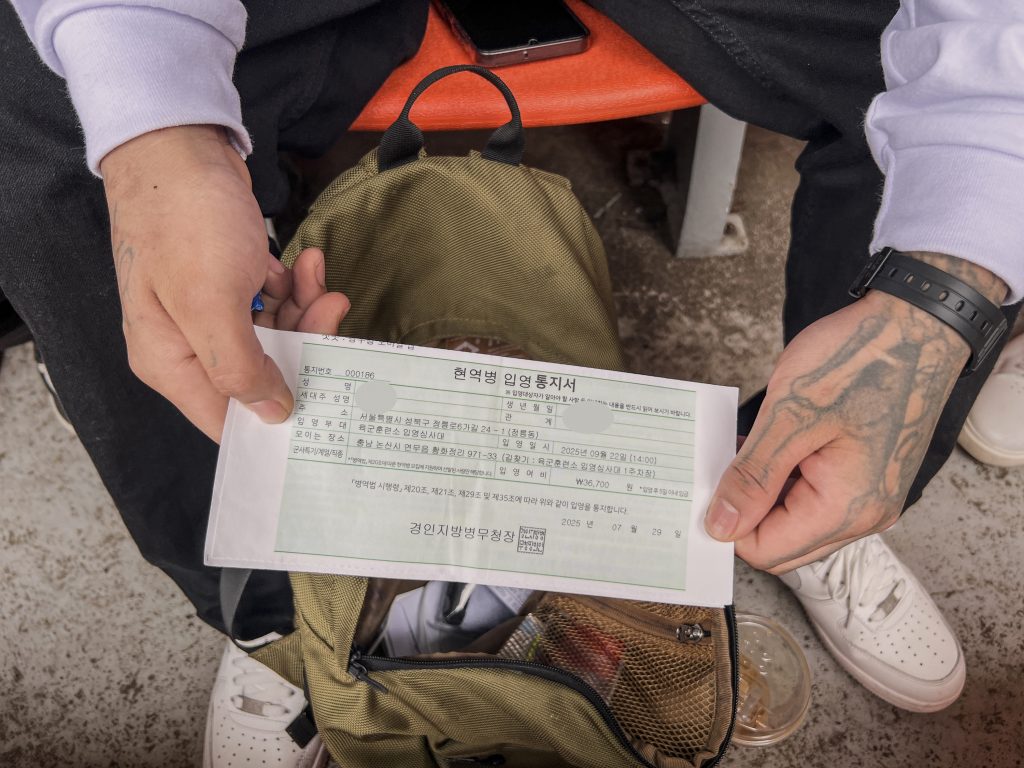

Among the newest arrivals is K.Y., deported only five months earlier and now preparing to enter the Korean military. With the shelter’s help, he found temporary housing and a measure of stability before enlistment.

A Stranger in Uniform: The Story of K.Y.

When 28-year-old K.Y. arrived in Korea, he did not understand the language, the systems, or even the basic expectations that the country held for him. He had lived in the United States since age two and assumed he would spend his entire life there. Instead, on April 28, he stepped off a plane at Incheon Airport as a deportee—alone, unable to speak Korean, and carrying only a scrap of paper with a phone number a pastor had given him in Los Angeles.

The World Cross Mission took him in, giving him temporary stability while he tried to understand what came next. What awaited him was something he had never imagined: military service.

Korea enforces mandatory conscription for all men between 18 and 35, and K.Y. was no exception. Barely five months after arriving, he received his draft notice.

On September 22, outside the Army Recruit Training Center in Nonsan, K.Y. stood among new recruits who were saying goodbye to their families. He held his phone tightly, trying one last time to reach his wife in Los Angeles. “It’s night there,” he said, speaking slowly in Korean. “She’s probably putting the baby to sleep.” He tried to smile, but the effort showed.

When loudspeakers instructed recruits to “fall in,” he did not recognize the word. As others jogged toward formation, he looked around with uncertainty, then followed. His arms, covered in tattoos, and his hesitant Korean set him apart, but what marked him most was the sense that he was beginning a life in a country that felt entirely unfamiliar.

“I always thought of myself as American,” he said. “My language, my habits, everything. But America didn’t see me that way.”

K.Y. said he still does not fully understand how he ended up undocumented. He remembers being a child and not understanding the explanations his father gave in Korean.

“I didn’t know what ‘status’ meant,” he said.

In Los Angeles, he had been trying to stabilize his life. He earned a welding license and was recently hired at a factory in Koreatown. With a wife and a young child to support, he said he wanted steady work and a routine he could rely on.

He was arrested by ICE on his way to that job. No explanation was given.

During his nearly yearlong detention, he married his girlfriend—now his wife—who visited him at the facility. She later applied for a spousal green card on his behalf, but the case stalled, and he remained in custody.

“My whole life was in L.A.,” he said. “My family, my friends, my job. I felt like I was being taken away from everything at once.”

Then, without warning, ICE officers escorted him onto a flight to Korea.

At the airport in Incheon, U.S. personnel handed him over to Korean officials and left. “It felt like being abandoned,” he said. He approached strangers, mixing English with gestures to ask if he could borrow a phone. Eventually he reached the number on the paper—the World Cross Mission—and found his way to the shelter.

For 147 days, he lived as a foreigner in the country where he held citizenship. His appearance often drew attention. His arms and body are covered in tattoos, and his Korean is hesitant. On public buses, people avoided sitting near him, even when seats were empty.

“People stared at me,” he said. “No one talked to me. It felt like I didn’t belong.”

In the car on the way to the training center, K.Y. scrolled through photos saved on his phone. They were drawings he had made on his own over the years: detailed pencil portraits, flowers, faces imagined from memory. He had never taken art classes or shown the work to anyone. Drawing, he said, was something he did quietly, by himself.

After Prison, Before Belonging: The Story of J.K.

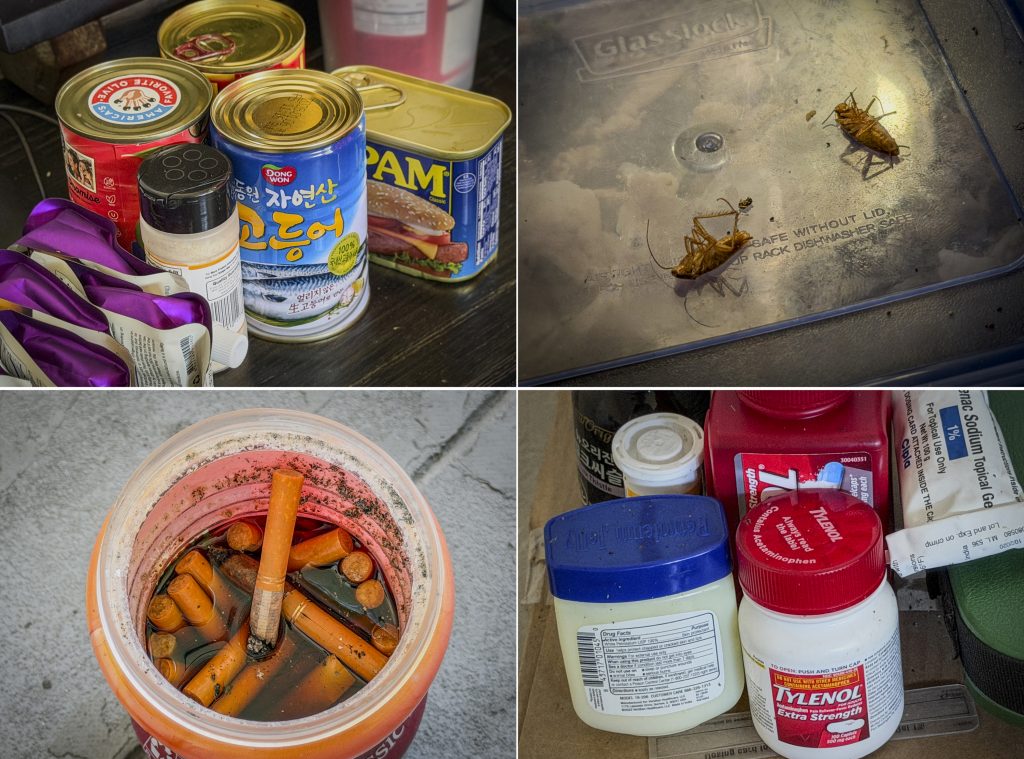

On a weekend in September, 51-year-old J.K. sat staring at his phone, searching for something on the screen. His fingers moved slowly, uncertainly. It was clear he was still learning how to use it.

“Korea is a place where you need a transit card just to get around, and almost everything requires phone-based verification,” he said. “It’s a highly digital society. I don’t really know how to use a smartphone yet, so I’m learning by watching YouTube.”

There is a reason even basic technology feels unfamiliar. J.K. spent 25 years separated from society. In June 2000, he was implicated in a drive-by shooting and murder in Los Angeles’s Koreatown and was sentenced to a minimum of 50 years to life in prison.

He served his sentence in the California state prison system, including at Fresno Valley State Prison. Over time, he was recognized as a model inmate and was eventually granted parole. He was released this past April. By then, the world he reentered bore little resemblance to the one he had left behind.

Even after his release, freedom did not follow. In cases like J.K.’s, deportation does not replace criminal punishment. Instead, it becomes a second penalty imposed through the immigration system.

“As soon as I got out, ICE agents came and took me to the Port Isabel Service Processing Center in Texas,” he said. “I thought I would never wear handcuffs again, but they put them back on—along with shackles.”

While he was detained, ICE officials informed him that he would be deported to South Sudan within seven days.

J.K. is legally a Korean national. He has no ties to South Sudan. At the time, the country was designated by the U.S. State Department as a “Do Not Travel” destination due to civil war, violence, abductions, and human rights abuses. When he asked why he was being sent there, he said, no explanation was given.

Under U.S. immigration law (INA 241(b)), individuals subject to removal are to be deported first to their country of nationality or their last habitual residence. Exceptions apply only in limited circumstances, such as statelessness, refusal by the home country, or risk to life. None of those conditions applied to J.K.

“My father contacted The Korea Daily,” he said. “After the story was reported, the Korean government stepped in. I was removed from the South Sudan flight list just before boarding and issued a temporary passport. That’s how I ended up coming to Korea.”

J.K. arrived in Korea on June 27. His father, who had followed the deportation process closely from Los Angeles and traveled ahead of him, was waiting at the airport. When J.K. walked through the arrivals gate, his father embraced him and cried.

There was little time to recover from the reunion. About a month later, a letter arrived at the temporary residence his father had arranged. It was from the police, informing J.K. that he was listed as “wanted.”

“Because I left Korea when I was young, I never completed my mandatory military service,” J.K. said. “When I came back, the system flagged me.” Police came to the house, and the case was referred to prosecutors.

He said the matter is still under review and expects it will likely be resolved, as there was no intent to evade service. Still, the process forced him to recount his past in detail—including the crime that led to his imprisonment—to authorities he had only just encountered.

Life in Korea now exists in a careful balance. J.K. can attempt to start over, but the more he conceals his past, the more isolated he feels.

“When I apply for an ID card, open a bank account, or sign up for health insurance, people ask questions,” he said. “They wonder where someone my age has been all this time. If I tell them the truth, they’ll see me differently. So I don’t.”

He recently found work as an engine cleaner at an auto repair shop in Suwon, Gyeonggi-do. It has been five days since he started. His coworkers know nothing about his life in the United States. His monthly pay is 2.7 million won(about $1835).

“I boil tap water to save money,” he said. “I don’t know yet what I should do long-term, but I want to save and maybe start a business someday.”

He paused before adding one exception.

“I don’t think I’ll ever tell anyone who I used to be,” he said. “But if I meet someone I want to marry, I would tell her everything. Whenever that happens.”

A Life Reassembled, Piece by Piece: Jeong Jin-uk

After K.Y.’s departure for military training, the shelter returned to its usual rhythm. One of the men quietly moving through that space is 65-year-old Jeong Jin-uk, who arrived at Incheon Airport on September 9 with no luggage beyond the clothes he was wearing. He had lived in the United States since the late 1980s, working on fishing vessels and later taking whatever jobs he could find in New York. By the time he chose voluntary departure, Korea had become a place he no longer knew.

Jeong owns almost nothing. A worn T-shirt and a pair of slippers are the sum of what he brought back. Without the World Cross Mission’s help, he said, he might have become homeless the moment he stepped out of the airport.

In New York, Jeong worked steadily—day labor, restaurant work, grocery store. As he remembered those years, he took a slow drag from his cigarette.

“You don’t know how hard it is to live without papers,” he said. “There’s something inside me that still hasn’t loosened.”

He described the ways people took advantage of him: wages withheld, threats to report him, and no place to complain. “If someone wanted to make trouble for me, all they had to do was say I was undocumented,” he said. “I kept my head down because there was no other choice.”

He watched news reports about ICE raids with a familiar tightness in his chest. “It felt like the walls were closing in,” he said. “I didn’t think I could survive much longer.”

A Korean church in New York eventually purchased his plane ticket home. Jeong boarded the flight, unsure what waited for him in a country he had not seen in more than three decades.

Back in Korea, he says he has no clear sense of the future. “I don’t have dreams,” he said quietly. “I don’t even know what I’m supposed to do now.” The pain of leaving the United States—something he felt he had no choice but to do—still lingers. For now, he takes relief only in not having ended up on the street.

A Rebuilt Faith: The Story of Lee Bon

Another resident shaped by the shelter’s long history is 73-year-old Pastor Lee Bon, who first arrived there after completing a lengthy prison term in the United States. His path back to Korea was far different from that of Jeong or K.Y., but his struggle to begin again shares the same contours of displacement and return.

“Lee Bon” is not his legal name. He chose it after coming to Korea, explaining that “Bon” echoes the English word “born”—a reminder, he said, of starting over. Today, he serves at Incheon Haneulmun Church and works with the World Cross Mission to support others navigating deportation.

Before that turning point, he lived through a turbulent and violent chapter of his life. He still remembers the date: May 3, 1985. Enraged after his wife left him shortly after obtaining a green card—believing he had been the victim of marriage fraud—he filed for an annulment. When she later hired associates who threatened him to withdraw the claim, he reacted in anger and shot her.

Lee was arrested and sentenced to life in prison. He spent 21 years and nine months in the California state system, much of it in the Fresno Valley State Prison. Over the years, Korean American pastors visited him, advocating on his behalf. Their petitions eventually secured a parole decision, and in February 2007, he was released—only to be immediately deported to Korea.

He returned with no clear direction and no personal network. Pastor Ahn took him into the shelter, where Lee began studying theology. Over time he became a pastor and devoted himself to assisting people who arrive in Korea after long, disorienting years abroad.

“The American legal system is strict,” he said. “When you fall, there is no real second chance. And when people are sent back here, the Korean government doesn’t have much in place for them either. There is no program to teach language or culture, nothing to help them adjust. Even basic statistics about deportees aren’t well maintained.”

According to South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 70 Koreans were forcibly removed from the United States between 2020 and 2024. ICE, however, recorded 367 deportations over the same period. The discrepancy suggests that hundreds of people who arrived in Korea through deportation are living outside any formal support or tracking system.

Pastor Ahn and Pastor Lee have met many of them. For both men, the work is steady but emotionally heavy.

Lee recalled one of the cases he found hardest to forget.

“There was an adoptee,” he said. “His parents never fixed his immigration papers, and then they left him. He had left Korea as an infant through adoption and came back to a country he no longer knew. Later, he took his own life. That still stays with me.”

Learning to Start Over, Then Helping Others Do the Same: Park Jin-woo

Near Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, Gyeonggi-do, 53-year-old Park Jin-woo works as a manager at a small logistics company handling moves for U.S. military personnel. He has lived in Korea for eight years, ever since he was deported from the United States after 25 years there.

“Recently, two Koreans were deported from the U.S.,” he said. “I helped get them hired at our company. I know what it’s like to land here with no idea how anything works.”

Park entered the United States as a young man and eventually obtained a green card. In 2014, he was arrested on human trafficking charges. Prosecutors initially sought a 45-year sentence, but when the evidence for those allegations did not hold, his case was reduced to a prostitution-related charge. He received a seven-year sentence. He spent three years in detention, which counted as double under credit-for-time-served rules; an additional year completed the required term. By then, the first Trump administration was underway, and his case was transferred for removal.

Park was deported in 2017. He arrived in Korea with little understanding of the systems he had to navigate. Over time, he learned how to re-establish his identification, open a bank account, find housing, and start working again. He now uses that experience to guide others.

“To live in Korea, the first thing you need is a national ID card,” he said. “But most deportees don’t even know where to go or what documents they need. I’ve done all of it myself, so I walk them through the steps. I help them get their ID, their bank account, their residency. If they want to work, and most do, I help them find a job.”

Park speaks without embellishment, but there is an unmistakable steadiness in his commitment to offering others the support he once needed.

On his left arm is a tattoo that reads “California,” inked after he returned. “It’s the place that meant something to me,” he said. He still lists Southern California cities—Los Angeles, Irvine, Gardena—with ease.

But when asked if he would return to the United States if allowed, his answer was immediate.

“No,” he said. “People think America is a country of immigrants. But who’s making all those ‘Made in USA’ products? Immigrants. They work hard, and the government pushes them out. I don’t think America is a country of immigrants anymore.”

He Can Travel Anywhere—Except Home: The Story of Park Sae-jun

Among the people trying to rebuild their lives in Korea is 55-year-old Park Sae-jun, a U.S. Army combat veteran whose deportation drew national attention last June. After The Korea Daily reported on his deportation, Park was referenced earlier this month as a deportation case during a House committee hearing, where he also participated via a virtual appearance.

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem came under pointed questioning from Democratic lawmakers over the administration’s aggressive immigration enforcement, including whether U.S. military veterans have been deported as part of the Trump administration’s crackdown.

During the exchange, Rep. Seth Magaziner (D–Rhode Island) cited the case of Park Sae-jun, a U.S. military veteran who was deported despite his service record. He said Park struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse after returning from military service, and was arrested in the 1990s on minor, nonviolent drug-related offenses.

“He never hurt anyone besides himself,” Magaziner said. “He’s been clean and sober for 14 years.”

When we met at a café in Euljiro, Seoul, he spent a long moment looking out the window before speaking. The crowds, the buildings, the pace of the city all felt familiar yet distant.

“Korea may be my country,” he said, “but it isn’t really my home. My son, my daughter, my mother… they’re all in the U.S. I want to go back to where my life is.”

Park immigrated to the United States at age seven and lived there for 48 years. He grew up in Los Angeles, lived through the 1992 LA riots, and remembers watching his parents’ store burn. For him, the United States was where he became an adult, raised a family, and built a sense of belonging.

In 1989, he survived a gunshot wound in combat and was awarded the Purple Heart. But long after returning from service, he struggled with PTSD and briefly turned to drugs. He later served a sentence for those offenses, completed his probation requirements, and reported regularly to ICE under supervision. In Hawaii, he worked at a car dealership and raised his children. He believed he had moved beyond his past.

None of that outweighed one mark on his record.

“Deportation took everything at once,” he said. “My home, my family, my work… everything I cared about. Overnight, I was separated from all of it.”

He arrived in Korea on June 24. Since then, almost every part of daily life has been solitary.

“I went to a baseball game recently,” he said. “Of course, I went alone. I don’t know anyone here. Sometimes I’m fine walking around, then suddenly the loneliness hits hard.”

For a period, he said, he woke up in the mornings and cried for hours without knowing why.

What weighs on him most is not only the separation but the permanence of it. Deportees with certain convictions are barred from the United States for life. He can travel almost anywhere in the world—except the place he considers home.

His mother is aging in Hawaii. His daughter may marry someday. He knows he cannot be there for any of it.

“I’m fighting it legally,” he said. “Not for something extraordinary… I just want my ordinary life back. Dinner with my kids, seeing my mom. That’s all.”

After Deportation, Only Survival Remains: The Story of S.J.

For S.J., 55, rebuilding a life in Korea has meant starting with the most basic question: how to get through tomorrow. S.J., who requested anonymity, was deported in the winter of 2017 after living undocumented in Los Angeles and being arrested for drunk driving.

When we met outside Eung-bong Station on a drizzling afternoon, he stood silently under his umbrella, his expression difficult to read. Since returning to Korea, he has relied on day labor and lives in a shelter run by a Christian organization.

Each morning begins the same way: he opens an app on his phone to check if any short-term jobs are available.

“If there’s work, I go paint apartment exteriors,” he said. “If I can’t find work, I just lie down in my room all day. It’s hard to earn even 100,000 won(about $70).”

He has few social ties and meets almost no one. His days revolve around earning enough for food and lodging, and anything beyond that feels out of reach.

“Living like this… you don’t really have energy left for talking or laughing,” he said quietly.

His son lives in the United States with S.J.’s ex-wife. Asking about him during occasional calls is, he said, the only part of the week he looks forward to.

“I’m not a father he can be proud of,” he said. “I feel too ashamed to tell him to visit. I haven’t seen him in eight years. Things just grow more distant.”

He follows news from the United States—especially reports of ICE raids—with a reflexive sense of fear.

“When I see those stories, my heart still shakes. I know exactly what that fear feels like,” he said. “But even so, I tell people not to come to Korea. Even if you avoid ICE, life here is too hard.”

While he spoke, he kept checking his phone for job postings, switching between holding the umbrella and scrolling for updates. If he failed to secure a job that day, tomorrow’s meals would be uncertain.

Eventually, he paused.

“I think I want to stop talking now,” he said. His voice had grown flat, as if something had closed off inside him.

He walked toward the subway, shoulders slumped. Eight years after deportation, the weight of those years seemed visible in the way he moved—slowly, without expectation, carrying a life reduced to the most immediate needs.

Every Day Until Departure Is a Day of Fear: The Story of Woo Won-gi

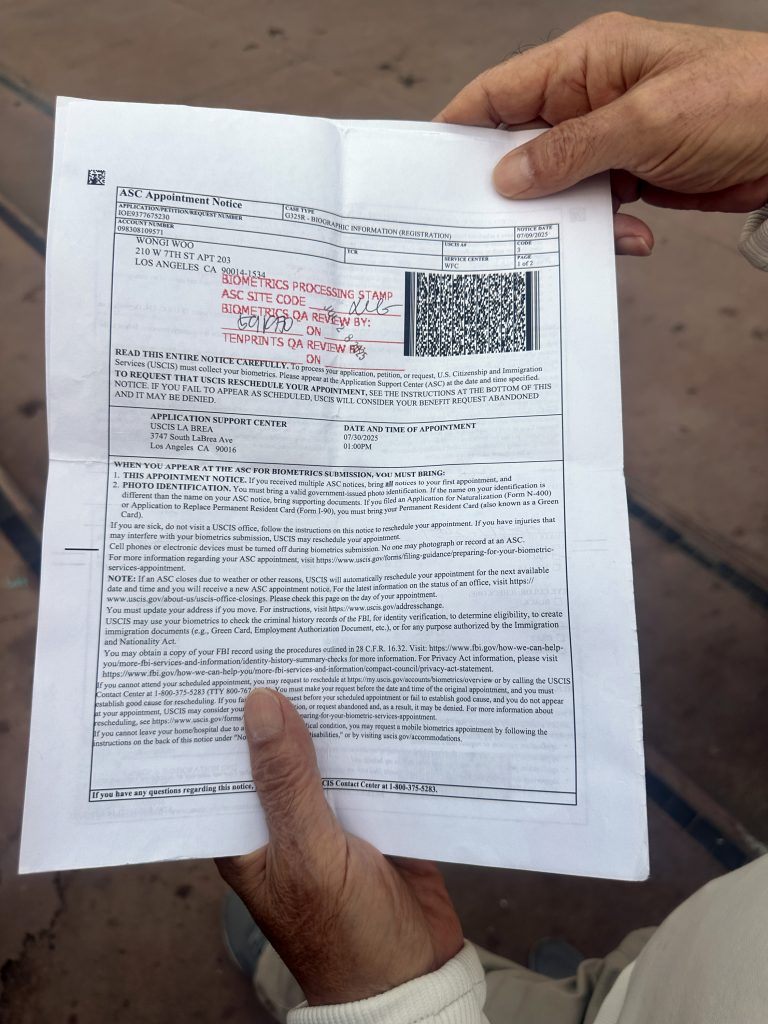

On July 28, in downtown Los Angeles, 75-year-old Woo Won-gi stood at a street corner and unfolded a sheet of paper he kept tucked inside his jacket. It was documentation from a recent appointment at a USCIS application support center.

“I applied for voluntary self-deportation,” he said. “They told me that if ICE stops me, I should show them this. They said I wouldn’t be detained if I have this paper. I carry it every time I go out.”

He put a cigarette between his lips and lit it. The smoke drifted upward between the buildings, carrying with it a long, audible sigh.

Woo longs to return to Korea, not because he expects an easier life, but because the fear of being detained in the United States has become overwhelming.

“I want to leave America as soon as possible,” he said. “I’m very scared.”

His English is limited, and the prospect of being taken to an ICE detention center—where he would not understand the language or know how long he might remain—terrifies him. “Rather than end up locked in there, I decided I should leave on my own,” he said.

Woo first arrived in San Francisco in December 2012 as a tourist. He met new acquaintances, many through gambling, and decided to stay. He talks openly about that period because, aside from overstaying his visa, he said he did not break other laws. He worked as a day laborer painting buildings and tried to keep a low profile.

“Other than gambling a bit with friends, I didn’t harm anyone,” he said. “I’ve lived with a clear conscience. I don’t understand why not having status means being treated like a serious criminal.”

He eventually sought help from the Korean American Federation of Los Angeles (KAFLA), after hearing that the organization advised undocumented immigrants on how to leave the United States safely through CBP.

“They said if you apply for voluntary self-deportation, CBP gives you a thousand dollars toward a plane ticket,” Woo said. “I don’t have the money for a ticket, so I applied.”

Five years earlier, he had cataract surgery through a nonprofit medical group in Koreatown. But after the Trump administration took office, he said, nonprofit services felt less accessible and moving around the city became riskier for undocumented immigrants.

“As I get older, my body hurts, and I’d like to see a doctor,” he said. “But that’s not easy. If I go out and ICE is there… I just can’t take that chance.”

He finished his second cigarette, stubbed it out carefully, and looked down the street.

“I’m too on edge to stay outside any longer,” he said, waving slightly before leaving. Woo keeps a small bag packed at home. As soon as CBP contacts him, he is ready to head to the airport. Until then, each day is one more day he fears being caught first.

Blind, and Afraid of Being Taken Away: Pastor Yang Jun-man

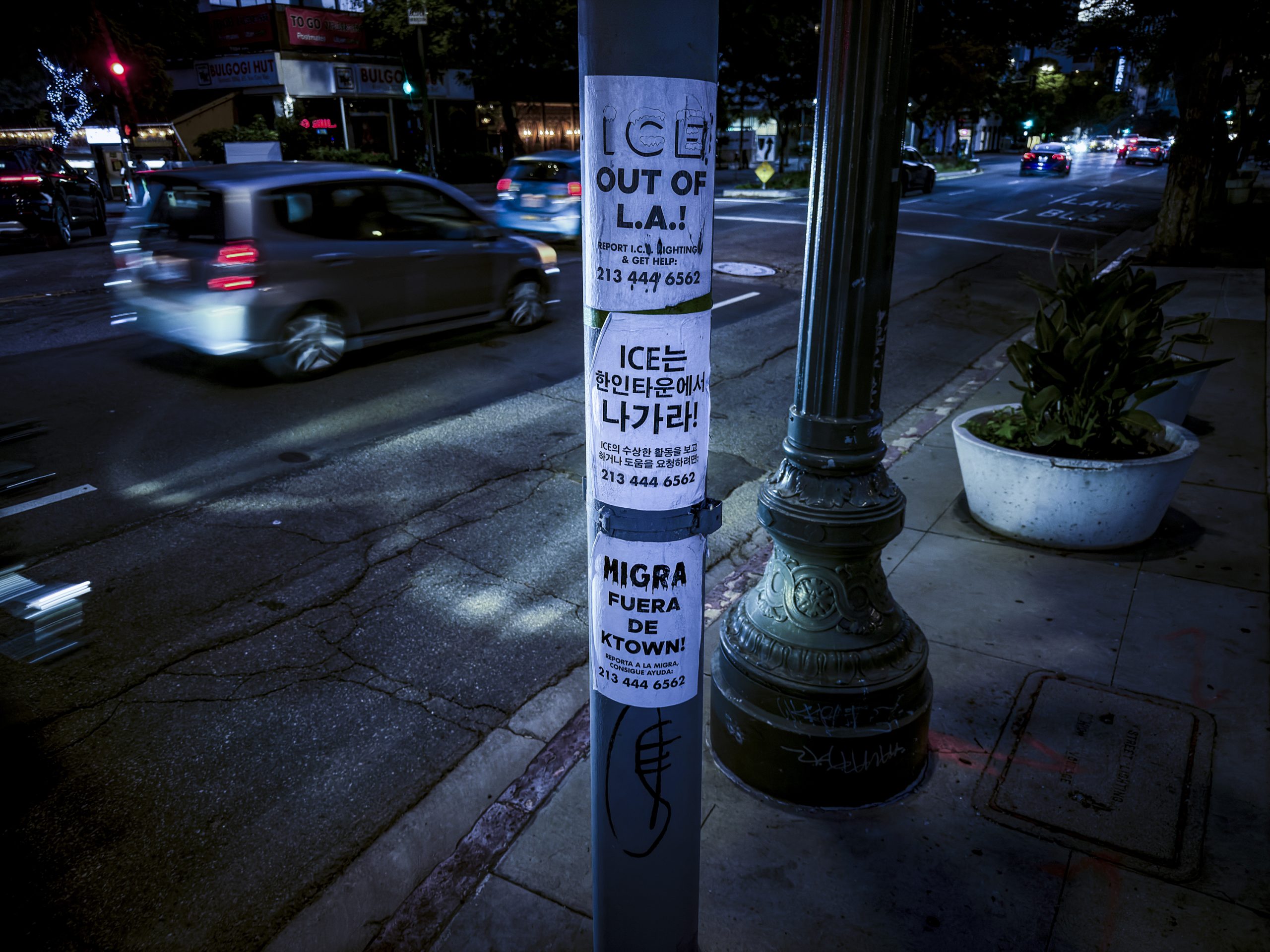

Pastor Yang Jun-man, 63, lives in Los Angeles Koreatown. He is blind, and that alone shapes every part of his daily life. But what frightens him most is the possibility that someone might suddenly grab him on the street, leaving him unable to resist or escape.

“Friends keep telling me, ‘Don’t go out if you can avoid it,’” he said. “Just yesterday, I heard ICE agents came right into the middle of Koreatown and took people. Whenever that happens, people message me right away. They know I can’t run if something happens.”

Yang is waiting for a decision on his green card application. Even traveling to a USCIS interview last September was difficult; he worried that if ICE stopped him on the way, years of waiting and paperwork would collapse immediately.

He had previously lived in the United States on a religious worker visa but did not realize it had expired. When the visa lapsed, he became undocumented without fully understanding that his status had changed. Later, his son enlisted in the U.S. military, became a citizen, and filed a petition for Yang to apply for a green card in 2016. The case has been pending ever since. He now has a work permit, but the green card itself has remained out of reach for nearly a decade.

“I had a domestic violence issue in the past,” he said. “And during the green card process, the address on my application was different from where I was actually staying. The officer said that was a problem. I think that’s why my case is still unresolved.”

Each morning he checks his mailbox for an approval notice. For him, a green card is not simply a legal document—it is the only thing that can lift the day-to-day fear that he might be detained and removed.

“I can work with my permit, but without a green card, I’m still afraid,” he said. “If ICE comes… I wouldn’t know what to do. I’m blind. If I were sent back to Korea, how would I survive? I need public benefits because of my disability, but I can’t get them without the card. So these days I don’t go out much. I mostly stay home.”

For Pastor Yang, safety depends on a single plastic card he has waited years to receive. Until then, he remains at home, hoping each day that the mailbox holds the document that could finally release him from fear.

A Door That Must Always Stay Closed

In a quiet residential neighborhood in the Los Angeles area, a Korean man in his seventies kept a cautious watch on the far end of an alley. Not far from his home, day laborers often gather near a Home Depot, a spot where ICE agents sometimes appear without warning.

“Nine of us live here now,” he said softly. “If people find out who stays in this house, we’ll be in serious trouble. I don’t have any ID. I’m very afraid.”

He described the house as a place that cannot be exposed to the outside world. From the street, it looks like any other home. Inside, it is where those who fear detection most come to hide—not because they want to live invisibly, but because any visibility could lead to detention and removal.

Rev. John Kim of Saint James Episcopal Church, who works with undocumented immigrants and unhoused residents in Koreatown, calls this house a “hideout.” It is not a formal program, nor a shelter with public funding. It exists for a single purpose: to keep certain people out of sight.

“There’s very little I can do directly,” Rev. Kim said. “The only thing I must do is never reveal this place. Keeping it a secret is how we protect the people here.”

Rev. Kim runs a separate shelter in Koreatown, but he says it has become too well-known and could draw attention. When someone’s identity must remain completely hidden, he sends them to the house in the residential neighborhood, where anonymity is their only form of safety.

For the people staying there, the risk of exposure is constant. They move as little as possible, remain quiet, and rely on one another. What should be an ordinary home has become a sealed space, where the outside world is seen as a threat rather than a refuge.

In this house, the door is not an opening to go out but a barrier that must remain closed. For those who live inside, the fear of someone unexpected walking through it shapes every hour of the day.

After Deportation, What Remains

For the people in this report, deportation did not mark an end, but a continuation of waiting, of uncertainty, of lives reorganized around what is missing.

Some wait for documents that may never arrive.

Others remain indoors, careful not to be seen.

Some learn new systems late in life, while others try to build a future without speaking about the past at all.

They are no longer part of the country they left, and not fully held by the one they returned to.

In between, they work, hide, wait, and adapt.

For now, that is what remains.

Yeol Jang joined The Korea Daily in 2007 and covers social affairs, religion, legal issues, and investigative reporting, including religious conflicts in Palestine and Israel, refugee camps in Hatay, Turkiye, and forgotten Asian immigrant graves in Hawaii and Portland. A UCLA graduate, he has received multiple honors, including the New America Media Outstanding Reporting Award and the INMA Elevate Scholarship.

Yoonjae Jung is a reporter at The Korea Daily covering society and local policy. He holds a degree in Economics from the University of California, Berkeley, and joined the paper in 2024. His reporting includes on-the-ground coverage of wildfire-affected areas, documenting Korean American residents who lost homes and neighborhoods.

Sangjin Kim | ✉

Sangjin Kim is a Los Angeles–based photojournalist at The Korea Daily. Born and raised in Seoul, he moved to the United States in 1999 to study visual communications. He has since documented immigrant communities and everyday life in Los Angeles, focusing on the city’s diverse neighborhoods through photography.