Graves and cemeteries are not simply places where people bury dead bodies. As illustrated in our report regarding Block 14 in Portland, Oregon, all artifacts in cemeteries and even the old moss on graves hold stories and meanings that could reveal the lives of the buried people.

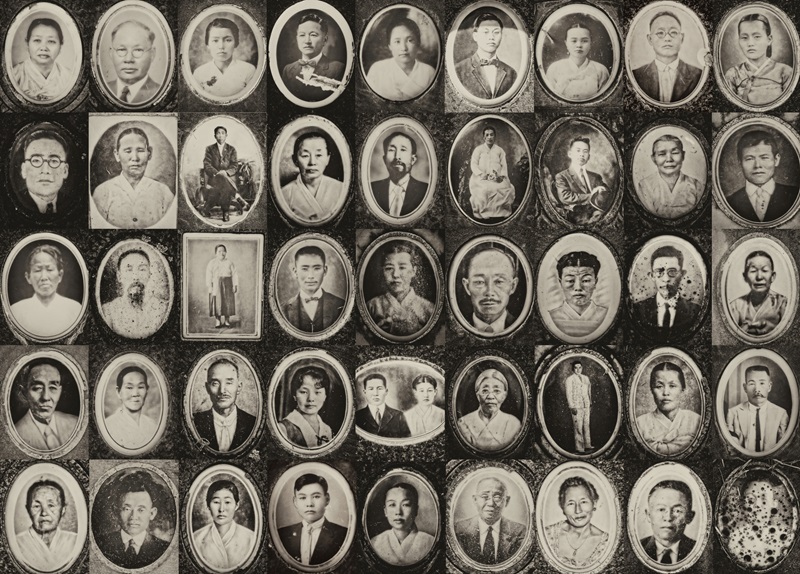

At Oahu Cemetery in Honolulu, Hawaii, many non-English names are etched on many tombstones. Some display images of Asian faces, showing both males and females. Notably, many Korean tombstones featuring female faces are paired with pictures of their husbands.

Gyomun Kim, a former pastor of the Kona Korean Mission Church, explained, “Most of these Korean wives arrived in Hawaii either accompanying their husbands, who migrated to the U.S. to work in sugarcane or coffee plantations, or independently to marry male workers in the plantations.”

Picture Brides, the Korean Rosie the Riveter

In 1921, Yamul Lee also arrived in Hawaii to marry a Korean worker who had come earlier to work on a sugar plantation. Lee had only seen her soon-to-be husband in a photograph while she was in Korea and decided to come to Hawaii for marriage. During that period, over a thousand young ladies came to Hawaii for the same reason. People refer to young women with such experience as “picture brides.”

Elder Hoon Park at Hilo Korean Christian Church, an 84-year-old retired physician who has lived in the Big Island, Hawaii, for more than half a century, described, “Many first-generation women immigrants to Hawaii were picture brides, and many people still remember Yamul Lee’s life story.” When Lee first set foot in Hawaii, she was just 18 years old.

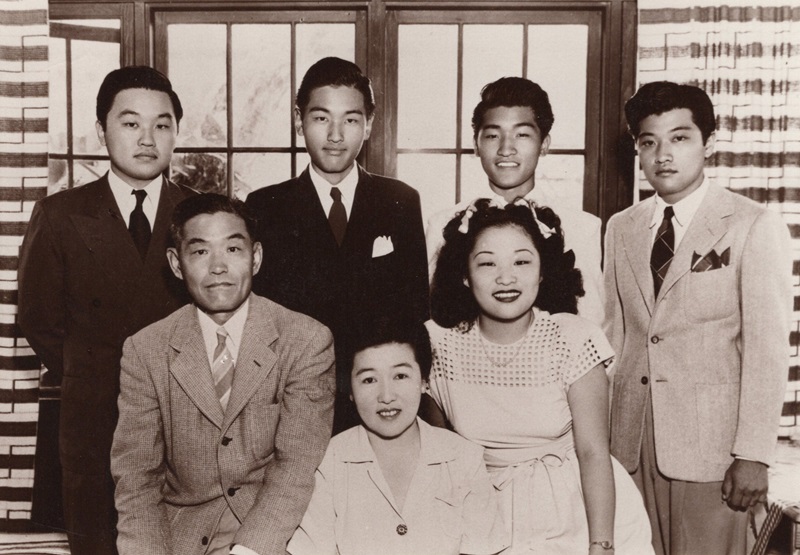

Unfortunately, Lee’s first husband was an alcohol and gambling addict, leading to their divorce. Afterward, she married another Korean worker, In-gi Kim, and adopted his last name, becoming Yamul Kim. She raised eight children, doing everything possible to support their children’s education up to college.

Many people still recall her as a kim chee (kimchi) seller in the early history of Korean immigration to Hawaii, as she sold kim chee, made with her own recipe, to her neighbors. One of her children, Harry Kim, who often helped his mother make kim chee, went on to become the mayor of Hawaii County and served in that position twice, from 2000 to 2008 and from 2016 to 2020. This is just one story among many of the picture brides.

Hawaii is the place where the history of Korean immigration to the United States began. According to the archive of the Center for Korean Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the first 102 Korean immigrants arrived at Honolulu Harbor on January 13, 1903, aboard the RMS Gaelic.

They were brought to the United States to work as cheap laborers on sugarcane, pineapple, and coffee plantations. The first wave of immigrants included not only male plantation workers but also 21 wives and 26 children under the age of 18. Until August 1905, approximately 7,400 Korean laborers immigrated to Hawaii.

Korea’s isolation policy and the opening to Western countries

The first Korean immigrants to Hawaii were people from Korea during the Joseon Dynasty (1392~1910). The late era of the Joseon Dynasty (later, Korea), spanning until the mid-19th century, was characterized by a strict isolation policy from the outside world. The isolationism aimed to safeguard the nation’s cultural heritage and traditions by blocking foreign influences that could compromise the country’s Confucian values.

The isolation policy of the Joseon Dynasty began collapsing in the mid-19th century due to external pressures from Western countries and Japan. In 1866, the French military occupied Ganghwa Island on the Mid-west coast of the Korean peninsula in response to the execution of several French missionaries. Then, the United States, responding to an attack on a U.S. merchant ship by Korean forces, launched a retaliatory military operation in 1871. Such continuous conflicts with Western countries resulted in the decline of Korea’s isolation stance.

A more critical turning point came in 1876 with the signing of the Treaty of Ganghwa between Korea and Japan, which unlocked three Korean ports for Japanese trade and bestowed extraterritorial rights upon Japanese citizens in Korea. Subsequently, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce was established between Korea and the United States in 1882, through which the United States claimed comparable rights to American citizens.

In 1895, the Joseon Dynasty reformed its governmental system through the Gabo Reform Movement and established a constitutional monarchy in Korea to modernize the nation and fortify its stance against foreign powers. However, the effort of the Joseon Dynasty to modernize the kingdom failed as Japan annexed Korea in 1910.

Amid these complex historical events on the Korean Peninsula, the history of Korean immigration to Western countries unfolded. During this period, the infusion of Christianity into the Confucian society played a critical role in both Korea’s international relations and immigration history.

First Korean immigrants to Hawaii

The first Korean immigrants to Hawaii were recruited by Pastor George Herbert Jones. He was sent to Incheon, Korea, as the pastor of the Naeri Methodist Church in 1892 by the Korean Mission of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States.

In 1901, Korea suffered greatly from a severe famine, and Pastor Jones, at that time, conveyed a message to Naeri Church members and churchgoers in surrounding areas that, if they worked in Hawaii, they would be able to attend church without any constraints, housing and medical expenses would be provided, and generous salaries would be given. Consequently, the initial wave of Korean immigrants embarked on their journey to Hawaii.

Pastor Eugene Han, the senior pastor of the Christ United Methodist Church in Honolulu, Hawaii — the first Korean church in the United States — described “the first immigrants had a pioneering mind and were strong-minded even within Korea because, at that time, the Joseon Dynasty severely oppressed Western religions. Many Western missionaries and Korean Christians were persecuted and martyred.”

Despite these challenges and the oppressive environment, the first immigrants from Korea demonstrated a pioneering spirit. They were resilient and determined. This resilience and strong-mindedness played a critical role in their decision to emigrate to the United States, seeking a place where they could freely practice their faith and pursue a better life.

The history of the first Korean immigration presents many similarities with the early history of the United States, particularly with the Pilgrims, in various ways. Both groups immigrated in search of better opportunities, seeking to escape economic hardships in their homelands, and shared a common desire for religious freedom.

“We work, work, work. I sleep only 2-3 hours a day.”

During the Joseon Dynasty, women’s lives were shaped by Confucian norms that subordinated women to men, emphasizing virtue, submission, and male heirs. Furthermore, all marriages were arranged marriages because the Confucian social norm strictly instructed the separation of men and women after 7 years old.

Despite prevailing gender inequalities in Korean society, the introduction of Christianity brought forth new ideas. According to Byongsun Lee’s study on Christianity and modernity in Korea, early Western missionaries to the Joseon Dynasty provided unprecedented opportunities for Korean women to acquire modern knowledge, assume leadership roles in women’s work, and play active roles in society.

This new concept of modern women was further reinforced through the establishment of women’s schools. Based on this enlightenment regarding women, some researchers argue that Christian women at that time had untraditional, independent, and progressive mindsets compared to other women in that male-oriented society.

Duk Hee Lee Murabayashi, director of the Korean Immigration Research Institution in Hawaii, explained, “The Korean women immigrants in the early period of Korean immigration to Hawaii, who were recruited by the Naeri Methodist Church and other churches and missionaries, were not traditional, uneducated, or passive women. Instead, they were more active and enlightened women as they embraced Christianity under the circumstance of the strict ban on foreign religions imposed by the Joseon Dynasty.”

Many picture brides were also working women, while the role of traditional women in Korea was limited to housewives due to the strong Confucian influence in the society. The lives of first-generation immigrants to Hawaii in the early 1900s were rather simple as they came to work in a foreign country where everything, like language, culture, and lifestyle, was different.

Men went out to work all day, and women cooked and cleaned their tents or very small rooms given to workers from their plantations. As imagined, their economic hardship was severe enough to drive them to seek any job opportunities or income-earning activities. Alice Chai’s direct interview article published in 1979 shows a Korean picture bride’s life, “We work, work, work…that time, I sleep only about two or three hours. That time, we were very tight, you know. For two or three months, we never eat meat, always eat only vegetables.”

Establishing the first Methodist church in the Big Island’s history

As the first Korean immigrants were sent by Naeri Methodist Church in Incheon, Korea, it is not surprising that they gathered together to worship together. Their gathering started in November 1903, the same year the first Korean immigrants to Hawaii arrived at the port of Honolulu. That first gathering was the first moment of the Christ United Methodist Church in Hawaii, and it is the first Korean church outside of Korea.

The contribution of Korean immigrants to the U.S. Protestant Church, especially within Methodist churches, is significant, particularly evident in Hawaii. Retired pastor of Hilo United Methodist Church, Mal Yong Yi, explained the church’s remarkable history, “If you visit our church’s website, you can see ‘Our church was founded more than a hundred years ago in Hilo, as a mission church for Korean plantation workers. It was the first Methodist church in Hilo before no one, even American methodists, made that effort to establish a Methodist church in Hawaii.”

From the early period of their immigration history, some Koreans moved from Oahu, the island having the city of Honolulu, to the Big Island for better opportunities. As they did in Oahu, Korean immigrants gathered together to worship together and finally established the first Methodist church on the Big Island. The U.S. protestant missionaries were first sent to Korea in the late 19th century. The evangelized Korean immigrants then delivered the gospel to people in the Big Island, Hawaii.

Educating new Americans

The dedication of Korean parents to their children’s education is a well-known aspect of Korean culture. Usually, Korean parents invest substantial amounts of money and effort in ensuring a high-quality education for their children. It was not exceptional among the first Korean immigrants in Hawaii.

Two years later, after the first 102 Korean immigrants arrived in Honolulu, more than 7,400 Koreans took their first steps in Hawaii until August 1905. As the number of Korean immigrants increased, on May 7, 1905, several members of the Korean Methodist Church had a meeting at the home of Methodist Superintendent John Wadman to ask the superintendent to establish a school for Korean immigrants, initially pledging $2,000.

Koreans were persistent in founding a school to educate their children, and finally opened the Korean Boarding School for Boys in the fall semester of 1906, which was financially and informationally assisted by the Hawaiian Evangelical Association and other Christian mission groups.

In the first semester, 65 students enrolled up to 8th grade. The school had three American and two Korean teachers and one Korean dormitory director. In 1907, it was recognized as a regular school, and graduates could advance to any high school. “The history of this school is also related to the establishment of South Korea, as Dr. Syngman Rhee, who became the first president of South Korea, was appointed as the school principal in 1913,” said Seo Young Lee, consul-general of the Republic of Korea in Honolulu.

Dr. Rhee soon changed the name of the school to Korean Central School (often called Jungang Academy) and accepted female students into the school. Thus, Korean Central School became the first co-ed school for Korean students both inside and outside of Korea. “Dr. Rhee examined the modern education system for Korea at that school in Hawaii. Later, this experience greatly contributed to implementing the modern school system in Korea,” said Bong Yong Park, president of the Peaceful Unification Advisory Council – Hawaii Chapter.

However, at that time, the education of female students was a violation of the agreement with the Methodist women’s missionary, which was the major sponsor of the school, because it was a school for boys only before Principal Syngman Rhee. Dr. Rhee had no choice but to rent a house near the school and move the female students to it. However, the house was too cramped.

Dr. Rhee appealed to Koreans to raise funds for a dormitory for female students and, as a result of Korean immigrants’ active participation in fundraising, purchased a house to use as a dormitory for girls. Later, the school raised more funds and separately established the Korean Women’s Academy in the fall semester of 1915 without any help from the Hawaiian Methodist Mission.

“Almost everyone participated in the fundraising. It was not just a one-time donation. They regularly shared a certain portion of their salaries to support Korean education, although their salaries were very low. The regular donation would not be possible if the wives did not voluntarily and actively support the school to educate their children,” explained Director Lee Murabayashi about the fundraising process among Korean immigrants.

The history of Korean immigrant schools in Hawaii is particularly meaningful in the context of women’s education and the adoption of the American curriculum. Due to the prevailing patriarchal Confucian tradition, women’s education was largely neglected during the Joseon Dynasty.

However, early Korean women immigrants to Hawaii, who were enlightened by Christianity, played a decisive role in actively contributing to the establishment of schools for women. Importantly, at the first schools for boys and girls, the curriculum adhered to the American school curriculum. English proficiency was emphasized during regular classes, with additional instructions in the Korean language and culture offered in the afternoon. This dual approach aimed to achieve the twin objectives of Americanization and the preservation of unique Korean cultural elements.

“We are Korean immigrants in Hawaii, but I am a U.S. soldier.”

Chan Jay Park Kim Jr. was born on August 19, 1929, in Hawaii, as the youngest son of Chan Jay Kim and Sarah Park Kim. Delighted to have the son, his father named him Jr., so the youngest son came to be known as Chan Jay Park Kim Jr. Later, he joined the U.S. Army.

After training, according to Director Lee Murabayashi, he had options for deployment between camps in Alaska and Japan. Chan Jay Jr. discussed the options with his mother, and she suggested choosing Japan because it is close to Korea. She believed that Chan Jay Jr. might have the opportunity to visit Korea if he was deployed to Japan.

Taking his mother’s advice, Chan Jay Jr. decided to serve at the camp in Japan. Little did he know that his life would soon be entwined with a historic war, the Korean War. Shortly after his deployment to Japan, the U.S. troops stationed in Japan, including Chan Jay Jr., echoed the urgency of wartime preparations. As expected, orders were issued swiftly, and troops were mobilized to defend South Korea against the imminent threat from North Korea.

Since Chan Jay Jr. died in the Korean War, his mother has regretted her advice every day, as she believes what she suggested was a determinant in Chan Jay Jr.’s decision to go to Japan and death in the Korean War.

Although he passed away, he received several honors, such as awards and medals, including the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, Prisoner of War Medal, Korean Service Medal, United Nations Service Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Korean Presidential Unit Citation, and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal. His sacrifice and bravery, not as a Korean soldier but as an American soldier, are commemorated at the National Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., where his name was etched alongside other heroes who fought during the Korean War.

In Hawaii, the Korean and Vietnam War Memorial stands adjacent to the State Capitol building, which was dedicated on July 24, 1994. Its architecture comprises two curved walls of terraced granite pedestals, one for each war, featuring inscriptions of the names of individuals who lost their lives or went missing in action.

Each pedestal has an engraved name of the U.S. soldier from Hawaii who perished in the respective conflicts. The names of Korean American U.S. soldiers who served in these wars were etched on many pedestals. Chan J. P. Kim Jr. is also on one of the pedestals. “An old gentleman comes here roughly once a month and wipes all of these clean. It’s about time for his next visit,” said Sebastiano Vani, a security officer at the Hawaii State Capitol.

Korean immigration as a part of U.S. history

Hawaii was a kingdom and joined the United States on August 21, 1959, as its 50th state, while the history of Korean immigration to Hawaii began in 1903. Even before Hawaii became a state of the United States, Korean-Hawaiians made significant contributions to the community.

Korean immigrants initially came to Hawaii seeking economic opportunities. However, their roles in the process of modernizing Hawaii were monumental. They worked hard in the agricultural sectors, established an education system based on the principle of equal opportunities across genders, and served in the U.S. military.

Coupled with learning English and following the U.S. curriculum in Korean schools, Korean immigrants made a great effort to keep the Korean culture and introduce it to their new communities on different islands in Hawaii. This became a cornerstone of Hawaii’s multicultural education system that reflects a rich blend of different traditions, languages, and cultures, making it a dynamic environment for learning.

During times of war, Korean immigrants, like other immigrant groups, demonstrated their patriotism by serving in the U.S. military. The Korean War, in particular, demonstrates the involvement of many Korean Americans in the U.S. armed forces.

Although first-generation Korean immigrants in the early 1900s faced severe challenges, including economic hardship, language barrier, cultural differences, and discrimination and prejudice, their resilience and contributions to Hawaii’s modernization and cultural enrichment shaped the diverse and polycultural fabric of the United States.

Revealing the neglected U.S. history covered by old moss and dirt

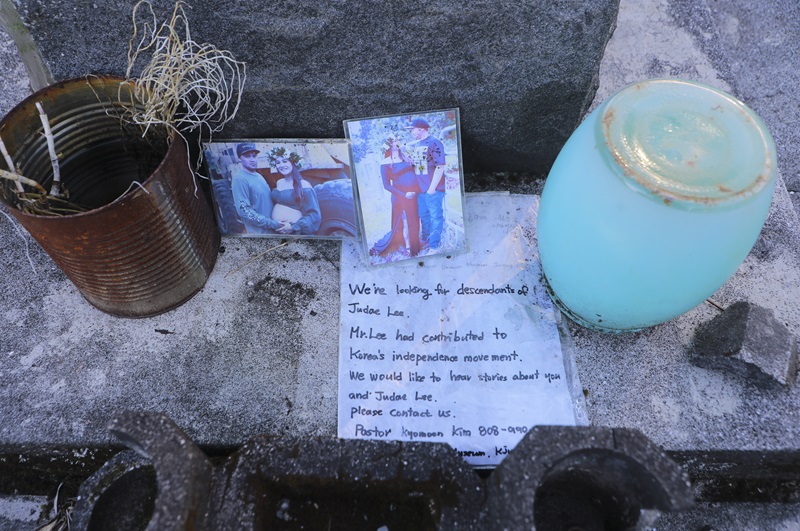

Near a small coffee plantation on the slopes of Hualālai Mountain in Hawaii, a winding path with steep and mossy rocks leads downward. Bamboos stand high, and square-shaped monuments blanketed in aged moss and dust are obscured within a bamboo forest. Upon closer look, hardly readable characters are etched onto these stones.

In retrospect, Elder Park of Hilo Korean Christian Church witnessed, “Until the 1980s, Koreans living in Hilo worked together to move the graves of early Korean immigrants to Hilo into cemeteries. However, no one cares about those graves now. They have been neglected for long. Most of their descendants already moved to the mainland or are no longer here.”

At a corner of Captain Cook, located in the mid-west part of the Big Island, scattered tombstones give visitors curiosity about who was buried in the graves. Among those uncared graves, some tombstones have Korean names. However, few know who they are, and little care is given by any one.

Although the graves have been abandoned, the tombstones seem to be attempting to tell travelers the stories of the people buried there, maybe from more than a hundred years ago when they first arrived in the land of hope.

The history of Korean immigration to Hawaii is not only the history of Koreans. It is a part of U.S. history, as the neglected and abandoned graves of early Korean immigrants are in the land of the United States. When the forgotten history becomes retold, a cornerstone of U.S. history will reveal its shape from old moss and dirt.

By Ryan Yeol Jang, Sangjin Kim, Mooyoung Lee (The Korea Daily)

and Do Kyun David Kim (Professor at the Univ. of Louisiana at Lafayette)

[jang.yeol@koreadaily.com, do.kim@louisiana.edu]