Editor’s Note:

This article was originally published on March 4, 2014, in The Korea Daily.

In light of Pastor John MacArthur’s passing on July 14, 2025, in Santa Clarita, California, we are republishing this exclusive interview for our readers.

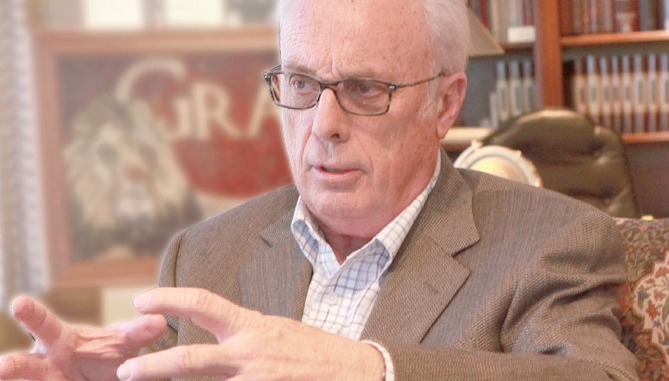

John MacArthur is frequently named by American media and churches alike as one of the most influential pastors of the 21st century.

We took a discreet look at the desk of one of America’s most prominent expository preachers. On the neat surface sat a single fountain pen and a Bible—an image that mirrors his discipline and convictions.

“I handwrite every sermon,” he said. When asked how long he prepares, he replied, “Usually about 20 hours.” Now 75 years old, he has served Grace Community Church in Sun Valley for 45 years—on the condition that he focus solely on preaching, abstaining from all administrative duties.

On February 19, he gave his first-ever exclusive interview to a Korean news outlet. Over the course of an hour and a half, MacArthur offered a piercing critique of the Korean church through the lens of American Christianity. He didn’t hesitate: “The church today has lost just one thing,” he said. “But it’s everything.”

It took America two centuries to lose its Christian soul. Korea didn’t even take two decades. Plagiarism scandals and $300 million mega-churches expose the raw ambition of the modern pastor. Search committees flounder because pulpits are now reserved for kings—or celebrities. A pastor’s calling is depth, not scale. Tend the flock, not the spotlight. The church must proclaim not what people crave to hear, but what they cannot afford to ignore.

Q: What has the modern church lost?

“The Bible. It is the absolute, non-negotiable value the church must guard. The very life of the church depends on it. We are meant to teach about Christ, to obey His words, and to follow Him. The core issue facing the church today is this: it must be biblical. God blesses His Word. The church is built on that Word.”

Q: What does it mean to return to the Bible?

“Every problem stems from the absence of Scripture. Instead of asking what the culture demands of the church, we must first ask: What does Christ require of His church?”

Q: The Korean church’s credibility has hit rock bottom.

(When told that a Christian Ethics Movement of Korea survey found only 19.4% of the public trusted the church, MacArthur nodded. “That’s an unsurprising result,” he said. He seemed well-informed about the Korean church, even bringing up Pastor Cho Yonggi’s embezzlement and tax evasion trial. He noted that he had criticized “un-Christian elements” of Cho’s ministry in his own sermons.)

“That’s not just a Korean issue—it’s just as true in America. The church has become trivialized. It’s lost its voice. In chasing the world’s approval, it has become indistinct from the world itself—no longer a sacred space, but just another part of the noise.”

Q: Why did churches chase the world’s approval?

“Because the idea of a ‘true church’ is at odds with postmodernism. The Bible, as an absolute authority, is no longer easily accepted. Today’s society is so individualized that people create their own worlds, their own truths, their own spiritualities. In a consumerist age built on materialism and relativism, people selectively adopt values as they please. The church, in trying to follow that current, became indistinguishable from it.”

Q: That’s a critique often heard in Korea.

“America has lost Christianity. It took 200 years. Once, Christianity undergirded American society and culture. But ‘Christ-centered’ became ‘Christian-influenced,’ and now it has deteriorated into something closer to neo-paganism. In Korea, the process seems to have ended before it even began.”

Q: What do you mean by ‘ended’?

“Korea’s Christian history is relatively short. But the church grew explosively and became a powerful social force. The problem is, that influence came before Christian values had been deeply rooted—either in the church or in society. In that inflated, unstable state, the Korean church was rapidly swept away by postmodernism. And in the process, it lost its essence.”

Q: Korea recently built a $300 million church.

(We explained the plagiarism controversy involving Pastor Oh Jung-Hyun and the Sarang Church construction scandal. MacArthur shook his head and let out a deep sigh. “Was it really $300 million?” he asked several times, visibly disturbed, before responding in a noticeably sharper tone.)

“There are far too many empire-building projects in Christianity today. In most cases, church expansion is directly tied to the pastor’s personal ambition. For many, the size of the church feeds their ego. If someone tries to build a $300 million church, they must ask themselves—honestly and biblically—what their motive is. And if they obtained their degree through plagiarism? That alone speaks volumes about their character.”

Q: So it’s unbiblical?

“I’m not familiar with Korean prices or economic realities, but even if some comfort for the congregation was the goal, does it truly require that much money? Imagine using that money to spread the Gospel to every corner of the world, or to help those truly in need. That thought troubles me deeply.”

Q: The Korean-American church has also faced pastoral hiring scandals.

(We explained how some pastoral candidates are chosen behind closed doors, how pastors leave without farewells, and how some pursue upward mobility from one congregation to another.)

“That happens in America too. When a pastor’s personal goals and ambitions outweigh the care of the flock, this is what you get. Over time, pastors become kings—or celebrities—and congregants begin to crave that. But a true pastoral calling happens only when the pastor, congregation, and church collectively seek God’s will through a transparent process, and joyfully agree.”

(He cited Acts 20, where Paul departs from the Ephesian elders with tears and blessings.)

Q: What should pastors pursue?

“Depth, not breadth. It’s entirely possible to grow a megachurch using charisma, cleverness, or strategy—without any blessing from God. But you can’t manufacture depth. Pastors must focus not on numbers, but on faithfully tending the flock entrusted to them. Depth in the Gospel glorifies God—and only God.”

Q: The younger generation is leaving the Korean church.

“Church must not become an event for them. It’s not enough to tell exciting Bible stories. Churches and families must partner to instill conviction and certainty in the Gospel through systematic teaching and sound doctrine—starting from childhood. That’s incredibly difficult. Which is why the burden on parents is heavier than ever.”

Q: But many parents face a disconnect from that ideal.

“Korean parents, in particular, seem preoccupied with having children they can be proud of—kids who get into top schools, earn lots of money, and succeed socially. That’s not inherently wrong. But if they’re secretly chasing honor or fulfillment through their kids, that’s deeply dangerous. That’s not what parenting is.”

(He said he’s heard much—through media and acquaintances—about Korea’s exam-focused education and intense parental pressure. As a fifth-generation pastor, he said the greatest gift he received from his parents was this: “My father was the same man at church and at home.” He emphasized: “Parents must not only preach the Gospel, but live it.”)

Q: Why are young people turning away from church?

“Because the church is focused on attracting them. It comforts them. It waters down the Gospel. But at some point, they’ll ask, ‘Why am I even here?’ This generation has the tools to build their own virtual realities and self-made values. The church must show them that Christianity is not a fantasy—it’s truth. It’s real. It speaks to life.”

Q: Some even leave church entirely.

(He prefaced his response by assuming the individual grew up in a church that preached the true Gospel.)

“That question begins with a sobering fact: most people in church aren’t true believers. A true believer might leave a congregation, but not the Church. If someone never knew Christ and was never raised in the Word, then of course they leave. They were never drawn to the core of the Gospel in the first place. The church failed them—it preached only what people wanted to hear, not what they needed to hear.”

Q: You’ve been a senior pastor for 45 years.

“People call me ‘senior pastor,’ but I’m sure it’s just because of my age.” (Laughs.) “I have no authority here. I’m a preacher. I teach the Bible. My authority comes only when I proclaim God’s Word. And even that authority is delegated—not from my experience or education, but from the Word of Christ alone.”

Q: Have you ever considered leaving?

“Ministry isn’t about me. A pastor exists solely for the sheep entrusted to him. How can anyone leave so easily? After 45 years, some people jokingly ask me, ‘Why have you stayed at one church so long?’” (Laughs.)

Q: That kind of longevity is rare in Korean churches.

(He emphasized that any pastoral authority must be checked. He prefers to call himself a “preacher” or “teaching pastor.”)

“Maybe people see me as senior pastor simply because I’ve been in the pulpit so long. But our church has over 40 elders—and I’m just one of them. We stand on equal footing.”

Q: In Korea, there’s controversy over clergy participating in politics.

“First, we must understand what government is. Public sentiment toward our current government here in the U.S. isn’t great either. Honestly, I believe some of what we’re seeing in Washington is God’s judgment on America. But even a bad government is better than no government at all. In any case, the role of Christian citizens doesn’t change.”

Q: What is that role?

(He emphasized that expressing opinions within legal and democratic boundaries is valid.)

“In the Roman Empire, citizens had no vote—no political influence. Yet Christians prayed for their leaders, submitted to them, and lived holy lives to testify to the Gospel. Today, we live in a democracy. We have the vote. We can stand up for biblical values through the ballot box. But when that strength turns violent, it ceases to be biblical.”

Q: Are there exceptions to submission?

“When the government commands what God forbids—or forbids what God commands. And if that disobedience costs us, we must bear it humbly. If the government shuts down our church or throws me in jail, I’ll go. But I won’t burn buildings or incite riots. They’re not enemies. They’re the mission field.”

About Pastor John MacArthur

President of The Master’s University, John MacArthur has authored over 150 books. His bestsellers—including Ashamed of the Gospel, Hard to Believe, and The Gospel According to Jesus—have sold over a million copies and been translated into Korean. His sermons reach 23 countries through his media ministry, Grace to You.

A Glimpse into the Life of Pastor MacArthur

Strong Ties to Korea, A Life of Simplicity and Humility

Our interview began two hours late. CNN had suddenly requested a live appearance. Before accepting, MacArthur apologized and said, “I can’t let this cause any harm to you. I’ll reschedule my afternoon so The Korea Daily has ample time for this interview.”

▶ His office was spare. A bookshelf, desk, and a few chairs. Beside one chair sat a portrait of Martyn Lloyd-Jones, whom he called “the pastor I respect most spiritually.” A black-and-white wedding photo of him and his wife Patricia stood prominently on the shelf. He mentioned the importance of family repeatedly.

▶ MacArthur is related to General Douglas MacArthur, who served in the Korean War. Grace Community Church, founded in 1956, sent its first missionary to Korea—Margie Farlie, who spent 54 years there.

▶ Some critics label him a fundamentalist or dispensationalist. Asked about this, he said, “I don’t want to defend myself. Judge me by Scripture. If I’ve erred, tell me. I care more about preserving God’s truth than protecting my own name.”

▶ A final message for readers: “The Bible teaches us that when we place our faith in Christ, death is no longer something to fear. It becomes the beginning of eternal life. I hope people will deeply reflect on that truth.”

▶ Grace Community Church offers a Korean-language site (www.gracetokorea.org).

![Police shooting of man in mental health crisis sparks scrutiny in New York NYPD body camera footage shows the victim whom a police officer fires four shots at the scene. [Screenshot from NYPD bodycam video]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/0206-mental-health-100x70.jpg)

![California moves to toughen DUI penalties, ending leniency Deputies from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) conduct a sobriety test. [Facebook capture]](https://www.koreadailyus.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/0205-DUI-100x70.jpg)