The Last Screen Still Lit

As single-screen cinemas vanish, an immigrant family and community keep a neighborhood theater alive

By Hankil Kang and Yoonjae Jung

Photography by Sangjin Kim

As single-screen cinemas vanish, an immigrant family and community keep a neighborhood theater alive

In the South Bay, single-screen movie theaters have been disappearing for years. Many have closed without notice. Some were converted into warehouses, offices, or chain stores. Others survive only as names people barely remember.

Gardena Cinema still stands.

Where the Lights Still Come On

On a Friday evening in November, people begin to gather behind a small shopping center in Gardena.

Instead of the bright, towering signage of nearby multiplexes, only a few aging red letters glow faintly in the dark.

Gardena Cinema.

The theater has no automatic doors and no marble lobby. Next to the entrance, a small ticket booth juts out, sealed behind thick glass. Customers step up and ask for a ticket. From inside, a single paper ticket slides through. The design and lettering have remained largely unchanged since the 1970s.

Through the glass door, an old popcorn machine is visible beside a worn concession counter. A small paper sign taped nearby reads: CASH ONLY.

The person who opens the doors, turns off the lights, and carries out the last trash bag at night is always the same.

She is the theater’s owner, manager, programmer, and concession worker. She is also the daughter of the immigrant couple who fell in love with this theater in 1976.

Her name is Judy Kim.

On weekends with scheduled screenings, Judy arrives in the afternoon. She organizes posters, checks concession inventory, and sweeps the old carpet one more time before the doors open.

For Judy, Gardena Cinema is not a place she can leave. It is home.

It is also the last remaining single-screen independent movie theater in the South Bay.

As neighborhood theaters across California closed one by one, Gardena Cinema remained in the exact location for 79 years. Within that time are layered a family’s immigration story, the memory of a local community, and the changing history of American moviegoing.

The Marquee, Changed by Hand

On Tuesdays, when no films are scheduled, Judy comes to the theater alone.

She turns on the light inside the ticket booth, takes a deep breath of outside air, and steps onto the sidewalk in front of the building.

“The day starts not with the screen,” she said, “but with the marquee.”

Along Crenshaw Boulevard, a white sign holds tightly packed plastic letters. Judy rides a small lift up to the board, bends at the waist, and replaces each letter by hand.

Even setting a single weekend title can take time. If the wind loosens a letter, she presses it back into place. If one breaks, she searches the upstairs storage room for a replacement that looks close enough. Her fingers are often covered in dust and grease. After rain, water collects between the letters and must be wiped away.

“When the marquee breaks,” she said, “we tape it or glue it ourselves.”

This is not an LED display changed with a button.

From a distance, it looks like an old theater sign. Up close, it shows the responsibility of human hands.

Above the traffic on Crenshaw Boulevard, old neon and newly replaced letters glow together — a signal that movies are still being shown here, now.

Born after the War, Built for the Neighborhood

The building that houses Gardena Cinema was built in 1946, shortly after World War II.

When it first opened, it was called the Park Theatre.

In the years following the war, the United States was expanding outward at a rapid pace. Suburban housing spread, cars became part of daily life, and shopping centers appeared alongside neighborhood movie theaters. Park Theatre was one of many such theaters built during that period.

It was a place meant for people living within a few nearby blocks—somewhere they could walk to.

Children lined up for Saturday matinees with allowance money in hand. Young couples came for first dates. Soldiers returning from the war, newly out of uniform, sat in the darkened auditorium and laughed freely for the first time in years.

As time passed, the theater changed hands more than once.

Some owners took over the small theater, hoping it would serve as a stepping stone to larger ventures, only to fail. Others let it go before their retirement savings ran out. The films on screen changed, and the titles on the marquee were replaced again and again, but the building itself remained in the same spot, growing older with each transition.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the way Americans watched movies was beginning to shift. Drive-in theaters multiplied. Later, multiplexes—housing several screens under one roof—began to dominate. Audiences moved toward larger screens, more comfortable seating, and a wider range of choices.

In that movement, many neighborhood theaters closed or were repurposed.

Gardena Cinema was not immune. Its heyday had long passed. With each new owner came the same question: Could this place be revived? Each time, the question was left unanswered, passed on to whoever came next.

And so, over time, the aging single-screen theater arrived once more at a moment of decision.

This time, the next family to step forward had come to the United States from Korea.

An American Dream Without Applause

In 1976, the theater represented both opportunity and risk for John Kim.

After immigrating from Korea to the United States, he moved from one small restaurant and shop to another, taking on whatever work he could find. It was a life shaped by making all-in decisions—putting everything he had into a single chance. But a movie theater was different. Once inside, it was not easy to leave.

“For our family,” he said, “it was another attempt—but it felt like the place where we had to put everything we had.”

His first exposure to theater work came not long after he arrived in Los Angeles.

In 1971, while working at a wig shop, he was introduced by a former supervisor from Korea to a job as a projection booth assistant at a downtown theater. Each morning, he opened the doors before dawn and cleaned the restrooms first.

Only after clearing popcorn scattered across the floor, discarded paper cups, and half-chewed gum could he go upstairs and touch the film.

“That was the order,” he said.

In that way, he learned the theater with his body—how film moved through darkness, how light spilled onto the screen.

In 1976, an opportunity arose for him.

The Italian American owner who ran a small theater in Gardena put it up for sale.

Once again, John gathered all his assets to assemble a $50,000 down payment, covering the rest with a bank loan and income from the market.

That is how the Kim family became an immigrant family that owned a neighborhood theater with about 800 seats.

By the time the theater came into the Kim family’s hands, it had already long passed its “golden age.”

“I thought once we took over, a bright future would be waiting,” he said.

“But when we actually opened the doors, there were so few customers. It was a really tough situation.”

Gardena Cinema had to contend with its aging layout and outdated facilities, as well as a shrinking audience.

When the Kims took it over, they had to relearn the film distribution system, the ticket-accounting process, and the tastes of the local audience.

Running a movie theater meant more than simply showing movies.

It meant fixing machines that no longer worked reliably. Clearing dust and trash that accumulated day after day.

When the movie ended, audiences filed out. What remained was always the same: crushed paper cups, popcorn on the floor, sticky soda stains, restroom tiles no one cleaned first.

John Kim stayed behind.

Near dawn, he emerged from the restroom carrying a black trash bag. Under a flickering fluorescent light, he paused and spoke quietly, almost to himself.

“Is this the America we dreamed of?”

He had crossed an ocean and carried the title of theater owner, only to end his days cleaning bathrooms. And yet, he could not let the work go.

There was no story of sudden success. Instead, there was repetition: cleaning and repairs, balancing expenses, adjusting showtimes. One day ended much like the next. The schedule remained the same. The cleaning was finished. The trash went out.

That was how the theater continued, maintained as an immigrant family’s version of the American dream.

When the Neighborhood Became the Audience

After the Kim family took over the theater, the most significant turning point began with a change in the audience.

Gardena is a city where Latino, Black, and Asian immigrant communities live side by side. During the day, many residents work in factories, warehouses, restaurants, and cleaning jobs. At night, they look for places where they can sit with their families and rest.

Some moviegoers were not fully comfortable in English, but Spanish-language dialogue and songs came easily. They enjoyed Hollywood blockbusters, but they responded more readily to stories shaped by the humor and emotional rhythms of home.

Over time, John and Nancy Kim began to notice that the faces coming through the doors were changing.

At a certain point, the theater began to revolve around the neighborhood itself.

Spanish titles appeared larger on posters. The Kims contacted distributors to secure films with Spanish dubbing or subtitles. Flyers were handed out at grocery stores, churches, and Latino-owned restaurants.

Inside the theater, English fluency was not required. No one was asked to explain their immigration status. A single ticket was enough.

For the Latino community, Gardena Cinema became more than affordable entertainment. It was a place where families could laugh together without feeling self-conscious or watched.

A theater run by one immigrant family had made room for others.

From then on, the theater was called “Teatro Variedades,” Spanish for “Variety Theater.”

What Remained Fell to the Daughter

The vitality of the Teatro Variedades years did not last.

A short drive away, larger, brighter, and more comfortable theaters began to appear. Multiplexes opened in nearby cities, offering expansive parking lots, reclining seats, and the latest sound systems. On weekend evenings, people naturally gravitated in that direction.

The lobby at Gardena Cinema grew quiet again.

Lines became less common, even on weekends. Weekday screenings were reduced to one or two showings. As revenue declined, the first things to be cut were staffing and programming. The gaps were filled by family labor.

“Maybe it’s time to close,” someone would say.

The thought began to circulate—moving back and forth between the ticket counter and the living room.

There were other options. The building could be leased out, providing steady rental income. A different business could be started. But this place held more than a theater’s name. It carried the family’s time, a child’s years growing up, and the memory of failures and repeated attempts.

And so, once again, the theater chose a quieter path: to endure.

The person who witnessed this period of change most closely was Judy Kim.

As a child, the theater was both playground and home. After school, she sat beside the ticket booth doing homework. When screenings ended, she followed her parents through the auditorium, picking up popcorn scattered across the carpet. Long before it was a workplace, the theater was simply part of her daily life.

At one point, Judy planned to leave.

She loved making performances and dreamed of becoming a Broadway producer in New York. When she left for college on the East Coast, she did not imagine that her life would lead her back here.

Over time, the tone of her parents’ phone calls began to change.

At first, the calls were casual check-ins. Then they grew more frequent, shorter, more urgent.

When Judy returned to Los Angeles and walked through the theater, she understood.

The theater was still standing, but there was no margin left. After a series of disputes and poor decisions, the family lost their house and their car. For a period, all four of them lived together in a small office on the second floor of the theater.

At the time, 101 Dalmatians was playing on the screen.

Judy said that even now, hearing the film’s title brings back the air of those days.

During that period, the theater and the family’s life fully overlapped.

Judy Kim eventually enrolled in law school.

“I thought I needed to understand the law to protect my family,” she said. “That’s why I went to law school.”

The theater could not stop operating. While preparing legal filings, Judy sat in the ticket booth selling tickets.

During that time, the family’s meals often consisted of 99-cent hamburgers from Carl’s Jr. Judy recalled that it was almost the only food they could afford. Sometimes they bought one and split it into two meals to get through the day.

The theater was barely holding on.

Losses in the Time of Closure

The biggest crisis came with COVID-19 in 2020.

The screenings stopped.

As the virus spread, movie theaters became “the first places to close and the last to reopen.”

The screen went dark.

The projector shut down.

Dust began to settle inside the theater.

The popcorn machine, once running every day, was covered and pushed to the side.

The fact that the theater had stopped revealed itself first through small, ordinary scenes like these.

Days without opening stretched into weeks, then months. The Kim family encountered a silence unlike anything they had ever known. Income dropped close to zero, but expenses did not stop.

“Rent, insurance, utilities, basic maintenance,” Judy said. “And above all, the family’s living costs stayed the same.”

Rather than closing the theater completely, Judy Kim chose to continue what she could. One option was drive-in screenings, where audiences watched films from their cars.

The change did not happen all at once.

Cars lined up in front of the screen, and sound traveled through radios. The lights came back on, and the nights were not fully dark again.

“I didn’t want to lose the fact that this is a movie theater,” Judy said. “Even with the doors closed, I wanted people to know that movies were still being shown here.”

During the pandemic, many neighborhood theaters across the United States closed permanently. Some buildings were repurposed. Others became chain stores, warehouses, or offices.

Gardena Cinema came close to the same fate, for a time.

In the midst of that, her mother Nancy’s health deteriorated.

The family’s life became a shuttle between the hospital, their home, and the empty theater.

“Mom was diagnosed with uterine cancer, and she went through chemotherapy and radiation,” Judy said. “Even after treatment, she always insisted on being here. We told her to rest at home, but she said she wanted to rest at the theater. So we ended up bringing blankets and everything here for her.”

Even while the doors were closed, the building never really left them.

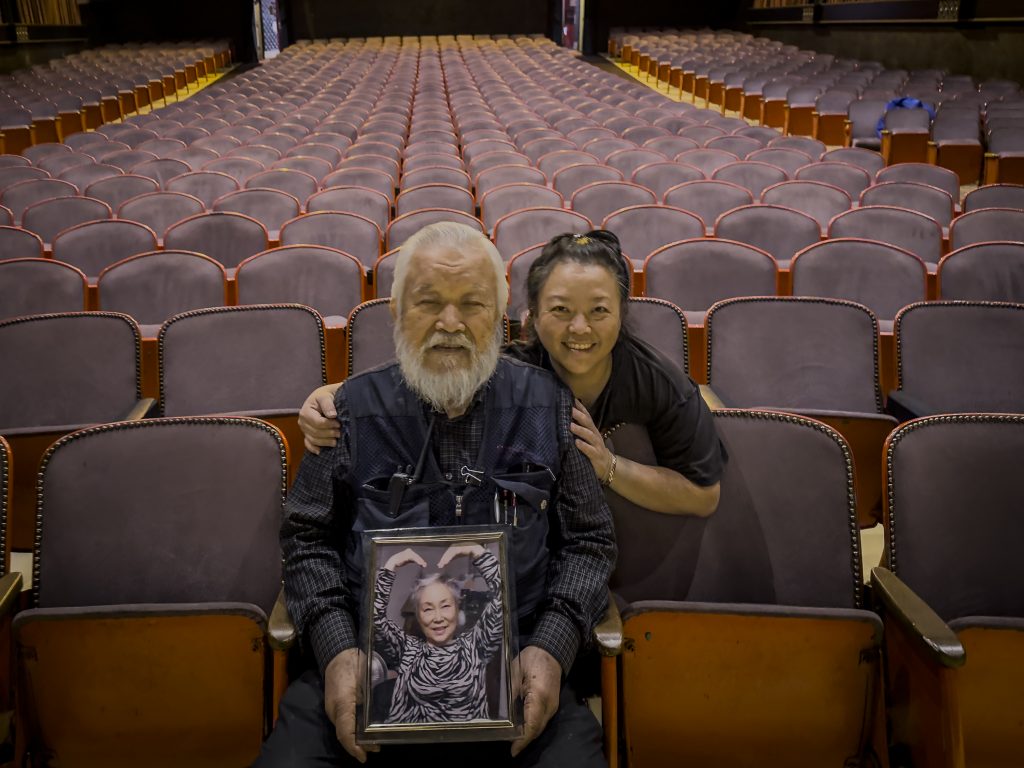

Judy’s mother, Nancy, died in May 2022 after battling cancer.

The doors stayed shut through the rest of 2020 and into early 2023.

A Theater the Community Refused to Let Fade

When Gardena Cinema reopened later in 2023, it could not return as it had been.

Judy could no longer run the theater alone.

What had once been carried by a family now exceeded the capacity of a single person.

But inside this building, the thread of memory had not yet broken.

The people holding onto it were Judy Kim and the others who kept moving through the theater.

The volunteers came from different backgrounds and places. Their ages and professions varied. What they shared was a belief that the theater should not disappear.

Bill DeFrance, 40, grew up in Torrance and first came to the theater as a teenager. He remembered watching double features with friends, then buying sodas at the shop next door. While attending film school, he passed the theater daily along Crenshaw Boulevard, imagining that one day he might screen a film there.

Several years ago, Bill created a YouTube channel documenting single-screen theaters in the Los Angeles area. Only two theaters responded: the Warner Grand in San Pedro and Gardena Cinema. He interviewed Judy, who that day was placing the letters “Birdemic 3” on the roadside marquee.

Soon after, Bill formally offered to volunteer. He took shifts at the ticket booth and box office and began discussing programming with Judy. The late-night screening series Gardena Cinema Late Nights grew out of those conversations.

“We’re still learning what works and what doesn’t,” Bill said, smiling. “Some movies connect. Others don’t at all.”

In this way, the theater began, once again, to gather people’s time.

On one side of the theater, another volunteer is making popcorn.

Suzy Evans, 72, introduces herself as the “popcorn man.” She has been coming to the theater since her teenage years. When Judy announced several years ago that she was looking for volunteers, she signed up without hesitation. Now, she spends most weekends at the cinema.

Suzy makes popcorn, hot dogs, and nachos. On slower days, she sits in the ticket booth.

“There are unusual customers here,” she said. “Independent filmmakers come through. I’ve even met directors who’ve won awards at Cannes.” She still remembers the atmosphere of a night when a silent film was screened with a live orchestra.

Even on nights without movies, people gather inside the building.

Every Tuesday evening, one side of the auditorium hosts an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Participants share only their initials, drink coffee, and take turns telling their stories. While such meetings are often held in church basements or community centers, this group chose Gardena Cinema.

The origins of the meeting overlap with the personal histories of Judy and Bill.

Judy lost a close friend to alcohol addiction. Bill nearly died early in the pandemic after falling into a coma brought on by heavy drinking. One day, the two sat side by side on the theater steps and talked. They decided to try holding a recovery meeting here. Both had experienced moments when films had helped hold them together.

Today, the meeting sometimes draws as many as 40 people. Many participants work in film, music, or the entertainment industry.

“This is a place where stories gather—not just movies,” Judy said. “For some people, this meeting may matter more than what’s playing on the screen.”

A Living Museum of Time and Memory

When the door to the projection booth is opened, two eras appear side by side.

Next to the digital projector stands an old film projector, still in place—the equipment Judy’s parents used for decades. Most of the 800 seats in the auditorium date back to the 1940s and 1950s. When bolts loosen or fabric tears, Judy and her father still pick up tools and repair them by hand.

On the second floor is a small room once known as the “crying room,” where parents would watch films through glass while holding crying infants. In an era before babysitters were common, parents brought their infants to the theater.

The space remains intact, a trace of a time when going to the movies was a family experience. This is why Judy has said she wants the theater to become a museum of sorts.

“Not a dead museum,” she said, “but a living one—where movies are still being shown.”

Nancy Kim died in May 2022 after a long battle with cancer.

On the day of her funeral, people gathered at Gardena Cinema. A photograph of Nancy was placed inside the theater. Neighbors and longtime patrons watched a memorial video together and recalled brief conversations once exchanged in hallways and aisles. Before taking Nancy to the cemetery, the family stopped at the theater one last time.

After that day, it became difficult for the theater to operate as before.

Nancy Kim’s grave sits on a sunlit hillside overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

Beside her name is a space bearing only the name John Kim.

Between them, the headstone holds photographs they took together, alongside images of the theater they spent their lives maintaining.

Arranged like frames of film, the theater appears within the same sequence as their lives.

In recent years, the event Judy has devoted the most effort to is Nancy Kim Day.

Held on her mother’s birthday, it serves as both a fundraiser and a way to mark the years the theater has endured in the South Bay. The film screened is Face/Off, Nancy’s favorite. Judy programmed it three times in one day, hoping that everyone who came could spend time with the movie her mother loved.

On the day of the event, the lobby was filled with food. People moved in and out of the auditorium holding paper plates, remembering Nancy. After Judy offered a brief greeting before the screening, applause followed. Those gathered were not just audience members. They were people remembering a family through the place that had held them together.

Calling the Past Back

Memory continues in other forms.

Free screenings were organized with filmmaker Sean Baker and Pluto TV.

A performance by the legendary punk band Circle Jerks.

Formed in the South Bay in 1978, the band took the stage.

The event began with a proposal from an outside promoter, Sister Midnight.

As the soundtrack album for the film Repo Man—in which the band appeared—was being re-released for its 40th anniversary, the organizers were looking for a venue where they could screen the movie and hold a live show together.

At first, they planned to hold the event at a nightclub in Hollywood, but the club could not accommodate a film screening.

They then searched for a venue that could host both a concert and a movie, and reached out to Gardena Cinema.

Adding to the connection, the band’s drummer, Joey Castillo, was from the neighborhood.

He had been coming to the theater since he was a child.

“They told me they hadn’t played in the South Bay in more than 20 years,” Judy said.

“That day really felt like a reunion. So many people were hugging and saying, ‘It’s been so long.’”

Under the lights, longtime fans nodded their heads together, while younger audience members filmed the show on their smartphones.

On the screen, images of 1980s Los Angeles flickered. In front of the stage, audiences from different generations stood together, nodding along.

So the Lights Will Stay On

These days, Gardena Cinema screens films only three nights a week, in the evenings.

It cannot run as many showings as a multiplex. Instead, Judy and the volunteers decide together what films belong in the space. One wall of the lobby is lined with old posters and photographs.

Judy knows the theater’s future can no longer be safeguarded by individual effort alone.

She helped establish the nonprofit Friends of Gardena Cinema and developed a plan to purchase the building, ensuring that the theater remains a community asset. The fundraising goal is $15 million.

“I want to make sure that after I’m gone,” she said, “this place doesn’t get turned into something else.”

Her father, John, is now in his eighties. He has lost sight in one eye. Most evenings, he sits quietly in the auditorium, watching as people order popcorn and walk across the worn carpet toward their seats. When the lights go down and the screen fills with light, the space still functions as a movie theater.

Many theaters across the South Bay have already closed. In some cases, even their names have faded.

But behind this small shopping center, beneath aging marquee letters that glow after dark, people still gather on weekend evenings.

(Right) Weeds grow through cracked asphalt in the aging parking lot, which John Kim regularly treats with herbicide.

Hankil Kang | ✉

Hankil Kang is a journalist covering social affairs with a focus on Korean American communities and related social issues. He provides in-depth reporting on topics affecting immigrant and minority populations. Kang earned a BA in Public Relations and an MA in Journalism and Mass Communication from the University of Georgia.

Yoonjae Jung is a reporter at The Korea Daily covering society and local policy. He holds a degree in Economics from the University of California, Berkeley, and joined the paper in 2024. His reporting includes on-the-ground coverage of wildfire-affected areas, documenting Korean American residents who lost homes and neighborhoods.

Sangjin Kim | ✉

Sangjin Kim is a Los Angeles–based photojournalist at The Korea Daily. Born and raised in Seoul, he moved to the United States in 1999 to study visual communications. He has since documented immigrant communities and everyday life in Los Angeles, focusing on the city’s diverse neighborhoods through photography.