The fundamental difference between bacteria and viruses lies in their methods of reproduction. Bacteria reproduce by splitting into two, creating another identical entity. In contrast, viruses require a host to reproduce. They must inject their genetic material into a host cell to produce new viruses. Consequently, viruses are destined to infect other living organisms to survive.

Most viruses do not kill their hosts. This ensures the host remains alive so the virus can continue to thrive. However, the rapid evolutionary pace of viruses sometimes leads to the emergence of monstrous variants. These variants have the potential to ruthlessly infect numerous hosts, causing mass causalities. When such a variant combines high transmissibility with deadly effects, it can result in a pandemic.

Historically, such variants have emerged randomly. However, post-Industrial Revolution livestock farming practices have increased the likelihood of new variants. Viruses now evolve faster, jumping between animals confined in close spaces. This has significantly increased the chances of a new “monster” virus emerging.

Recently, avian influenza has spread to dairy cattle in the United States. Earlier this year, American farmers noticed a drastic and inexplicable drop in milk production, with milk becoming unusually thick. This anomaly was reported to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) which found avian influenza virus in the cows’ milk. The virus has now spread to 12 states.

The highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 2.3.4.4b is known for infecting various animals, with some cases proving fatal. Seals, sea lions, and even polar bears have died from it. Cats have staggered and died, with the virus found to attack their brain blood vessels, causing blood clots. Three workers on dairy farms have also been infected.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently surveyed 187 infectious disease experts from 57 countries to predict the next pandemic. Influenza topped the list, with 79% of experts naming it the most likely pathogen. The deadly variant of this influenza has spread worldwide, affecting all mammals, including humans.

Since its detection in U.S. dairy cows on March 25, avian influenza has continued to spread for over three months. Is this the dawn of a pandemic, or an overreaction by a public still reeling from COVID-19?

Mammalian attack by avian influenza variant

The U.S. is currently experiencing a rapid spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza. Traditionally, bird flu starts in migratory birds like ducks and geese and spreads to poultry like chickens and turkeys. Due to its high transmissibility and lethality, poultry on affected farms are usually culled.

However, the current H5N1 variant spreading across the U.S. is unique, garnering significant attention from virologists. It has spread not only to poultry but also extensively to dairy cows. Initially detected in cows on March 25, the virus has now infected 115 cows across 12 states as of June 20.

The virus has been found in cow’s milk, prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to advise against consuming raw milk and to cook beef thoroughly. Three human infections linked to contaminated milk have been reported.

“H5N1, first detected in 2016 in China, has now spread to North America and South America,” said Junghoon Kwon, a Professor of Veterinary Medicine at Kyungpook National University. “The virus was initially found in birds in China, making it the endemic region for bird flu. China first attempted to eradicate the virus without using vaccines, but this approach was unsuccessful. As a result, they started using vaccines. However, the virus evolved rapidly, reducing the vaccines’ effectiveness. There are increasingly more viruses emerging from China.”

This virus has adapted to infect a wide range of mammals, raising concerns about a potential human pandemic. Although the pandemic potential is currently low, the rapid evolution of the virus and ongoing infections in mammals pose a significant threat. Scientists warn that the situation requires close monitoring and swift action to prevent a more dangerous variant from emerging.

The current spread of avian influenza in U.S. dairy cows highlights the ongoing risk of virus evolution and the potential for future pandemics. While the immediate risk to humans remains managed, the rapid evolution of the virus and the widespread infection of mammals underscore the need for vigilant monitoring and preparedness to avert a possible global health crisis.

The most notorious virus that plagues humanity is the influenza virus, commonly known as the flu. There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C, and D. Among them, type A is highly contagious among humans and has caused several pandemics.

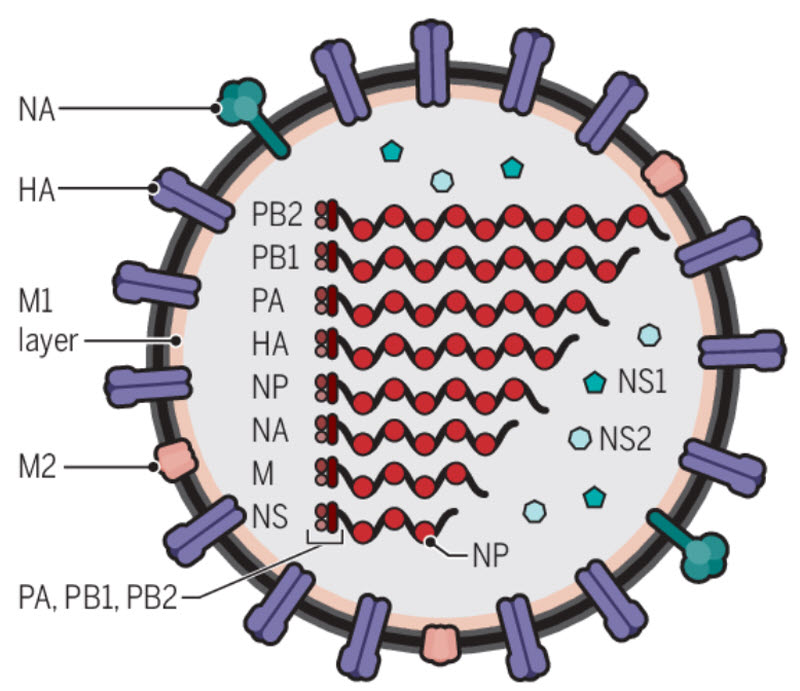

The severity of influenza A stems from its ability to undergo “assortment,” or genetic re-assortment. When two or more types of influenza A viruses enter the body, they can mix their RNA, leading to rapid evolution. This process can produce various strains, increasing both transmissibility and lethality.

“The influenza virus stands out from other viruses due to its segmented genetic structure, consisting of eight strands,” said Kwon. “When two strains of this segmented virus infect a single cell, they can mix. This results in a new, randomly mixed virus. To simplify, just as a person inherits half their genes from their mother and half from their father, creating a new individual that resembles both but is unique, viruses can also combine traits from both parent viruses or exhibit entirely new characteristics.”

The avian influenza currently spreading in the United States is classified as highly pathogenic H5N1 2.3.4.4b. The term “highly pathogenic” means that it can be lethal to chickens. Initially, this virus only affected birds, but it has evolved to infect mammals. In the United States alone, squirrels, skunks, polar bears, seals, and zoo tigers have been infected. There have also been cases of infection in animals living close to humans, such as mice and cats.

In South Korea, this avian flu led to the mass death of cats in June 2023, killing 38 out of 40 cats at a shelter. The virus found was H5N1.

Human mortality rate 52% virus

H5N1 is concerning because it can also infect humans. Until the 1990s, scientists believed avian flu posed little threat to humans. However, the virus evolved, and in 1997, a three-year-old child in Hong Kong died of pneumonia caused by H5N1. That year, 18 children in Hong Kong were infected, and six died, shocking scientists.

“This highly pathogenic avian influenza virus can be spread by a common enzyme called furing, present throughout the body,” Kwon explained. “When humans are infected, the virus is known to have a high mortality rate, particularly among younger individuals.”

By 2023, H5N1 had infected 882 people in 23 countries, with a mortality rate of 52%. Recent human infection cases in the U.S. involved respiratory symptoms like sore through and cough, while two individuals developed conjunctivitis after contaminated milk splashed into their eyes.

Preventing the spread of this avian flu in the U.S. can be surprisingly simple at the individual level. People should avoid consuming raw milk and instead opt for pasteurized milk available in stores. Thoroughly cooking beef is also recommended, as heat can easily kill the virus. Avoiding contact with wild birds and washing hands thoroughly after going outside are also important precautions. Birds such as sparrows, pigeons, and magpies have a very low likelihood of spreading avian flu, so there is no need for concern.

Professor Kwon further explains that while pigeons can be experimentally infected, they do not spread the virus asymptomatically like some wild birds do, making them less dangerous. Similarly, sparrows can get infected but are not known to play a significant role in spreading the virus.

Fortunately, H5N1 has a very low likelihood of respiratory transmission. Unlike highly contagious airborne viruses like COVID-19, H5N1 is primarily transmitted through bird droppings or saliva. In cows, the virus can be transmitted to humans through milk. Thus, H5N1 does not yet have the ability to attach to and infect human respiratory systems.

However, the concern lies in the word “yet.” Given time, viruses can evolve to adapt to humans and spread more effectively. H5N1 has already acquired the ability to infect mammals beyond birds.

Professor Kwon mentions that in 2012, research teams in Japan and Europe used ferrets as models to study H5N1 transmission to humans. After around ten transmission cycles, the virus underwent essential mutations, enabling it to spread through the air between ferrets. This raised significant concerns and sparked considerable debate. Based on these studies, there is a potential risk that the virus could quickly adapt to humans after a few outbreaks.

Surging raw milk consumption

One reason the U.S. struggles to control the virus is its political landscape. Currently, trust in the government in the United States is at an all-time low. Americans neither believe nor follow the federal government’s statements.

The CDC and the USDA are currently investigating dairy farms. However, farm owners are reluctant to acknowledge the presence of avian influenza on their farms. Due to the uncooperative attitude of the farms, the data collection has been significantly inadequate.

In the U.S., where state government authority and industry lobbying are powerful, federal agencies cannot enforce everything.

The American milk-related associations continue to distribute raw milk even after the outbreak of avian influenza. In states where raw milk sales are legal, it is still available for purchase. Right-wing media also promote the consumption of raw milk, claiming that the avian influenza is a government conspiracy.

The only action government agencies can take is to prevent the interstate distribution or transportation of raw milk.

In the U.S., raw milk consumption surged following the detection of avian flu in dairy cows. Despite warnings from the CDC not to consume raw milk, sales increased by 21 to 65% compared to the same period the previous year.

Scientists worry that farms may become large-scale laboratories where viruses mix and evolve. If H5N1 is not eradicated early, it could continue to evolve among animals like cows, cats, and mice, posing significant risks. Many argue that the experiment must be halted before a more potent variant emerges, but the future remains uncertain.

“All human influenza viruses, including seasonal flu, originated from avian viruses,” said Kwon. “Thus, the potential for H5N1 to change is substantial. Pigs, for instance, have both 2,3-sialic acid and 2,6-sialic acid receptors, making them a mixing vessel for bird and human influenza viruses. The 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic, which originated from pigs, highlights this risk.”

The 7-1-7 principle is crucial for responding to infectious disease outbreaks. This principle involves detecting the outbreak within seven days, notifying public health authorities within one day, and completing initial responses within seven days.

Professor Kwon emphasizes the importance of early response to infectious diseases to prevent their spread. “South Korea has already started monitoring cattle for infections,” he said. “The probability of the U.S. virus entering South Korea cannot be ruled out, as wild birds can carry the virus from the U.S. to South Korea, particularly in regions like Alaska where birds from both countries meet.”

The collapse of the 7-1-7 principle in the U.S. and the prolonged situation highlights the consequences of eroded political trust. Observing the current state of the U.S. offers valuable lessons for us.

BY JUNGBONG LEE, SOOKYUNG CHUNG, GAJIN LEE, JIEUN PARK, YOUNGNAM KIM [mole@joongang.co.kr]