The idea of a 50-year mortgage has been floated, pitching it as a way to make homeownership more affordable. But a closer look at the numbers and structure shows that such ultra-long loans could nearly double total interest costs, slow real wealth-building, and push more risk onto households and taxpayers.

On the surface, a 50-year mortgage would lower the monthly payment. However, experts warn it can become a long-term “financial trap” that forces borrowers to pay far more interest over time.

Christine Shin, secretary general of the Korean Real Estate Brokers Association of Southern California, said that stretching a loan from 30 to 50 years does not dramatically reduce the monthly payment but does dramatically increase interest. She called it a situation where borrowers end up paying “an absurd amount in interest alone.”

Using recent data from the California Association of Realtors (CAR), the article compares different loan terms for a typical home. In the third quarter, the median single-family home price in Los Angeles County was $954,130. With a 30% down payment, the remaining loan balance would be $667,891.

If that balance is financed with a 15-year fixed-rate mortgage at 6% interest, the total interest paid is about $346,597, for a total repayment of roughly $1,014,488.

On a more common 30-year loan at the same 6% rate, the borrower pays about $773,673 in interest, for a total of around $1,441,564—already more interest than principal.

With a 50-year mortgage, the math becomes far more extreme. Interest alone climbs to about $1,441,595, and the total repayment exceeds $2.1 million. The monthly payment would be only about $500 less than the 30-year option, but the borrower would end up paying nearly twice as much interest as the original loan amount.

Ultra-long terms also create serious equity problems. A 15-year borrower in Los Angeles County would repay about $376,363 over the first 10 years and build substantial equity in the home. With a 30-year loan, the borrower would repay about $108,961 in that same period.

With a 50-year mortgage, after 10 years the principal would shrink by only $28,901. In other words, a decade of payments barely reduces the actual debt.

The average U.S. homeowner keeps a property for about eight years. For a 50-year borrower who sells after eight years, the picture is even worse. Out of the $667,891 financed (after the 30% down payment), only about $22,000 of principal would have been paid off. The borrower would have spent years making payments but would still owe almost the entire original loan balance.

If that homeowner then loses a job, needs to move, or faces another life change that forces a sale, the proceeds from selling the home may not fully cover the outstanding mortgage. In that case, years of payments would leave almost no net asset. If home prices fall even 5%, the borrower can quickly end up with negative equity, owing more than the house is worth.

Jee Lee, director of Shalom Center, an Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-approved nonprofit, noted that a mortgage is supposed to help people own their home through ongoing payments. He argued that a 50-year mortgage is closer to “renting and maintaining” a house than truly owning it. He added that someone who takes out such a mortgage at age 40 would be 90 by the time it matures, calling into question whether it really serves the goal of homeownership.

Experts also warn that a 50-year product would require heavy government involvement. The standard 30-year fixed-rate mortgage exists today because of large-scale support and guarantees from federal programs. FHA mortgage insurance, federal loan guarantee programs, and loans backed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) all help push down interest rates by shifting risk onto the government.

Key players such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored mortgage agencies, buy large volumes of loans from private lenders and repackage them as securities. This system has allowed the 30-year mortgage to become standard, but only because the federal government assumes much of the underlying risk.

A 50-year mortgage would almost certainly demand even stronger government support and guarantees. Analysts caution that this would increase the chance of large-scale bailouts if the housing market turns down, with taxpayers paying the bill while lenders and investors are protected.

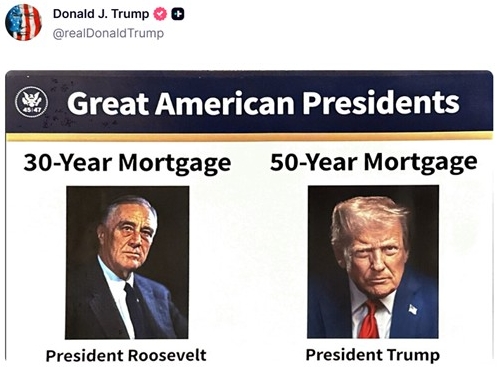

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, introduced under Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940s, is often praised as a New Deal tool to help ordinary families buy homes during and after the Great Depression. But critics say it also entrenched a debt-driven financial system dominated by large institutions.

According to those critics, a 50-year mortgage would go even further in that direction. If ultra-long loans become common, banks and homebuilders could sell more properties and collect interest over far longer periods, while households carry heavier long-term debt loads.

The proposed 50-year mortgage might offer lower monthly payments in the short term. Yet experts say it would cause total interest costs to surge over the life of the loan, encourage more speculative demand for housing, and likely push home prices higher. The result would be larger overall debt burdens and slower real wealth accumulation for families.

“On the surface, a 50-year mortgage looks like relief,” one expert concluded. “In reality, it asks the country to take on unprecedented levels of risk—and in the end, it is consumers and taxpayers who will pay the price.”

BY HOONSIK WOO [woo.hoonsik@koreadaily.com]